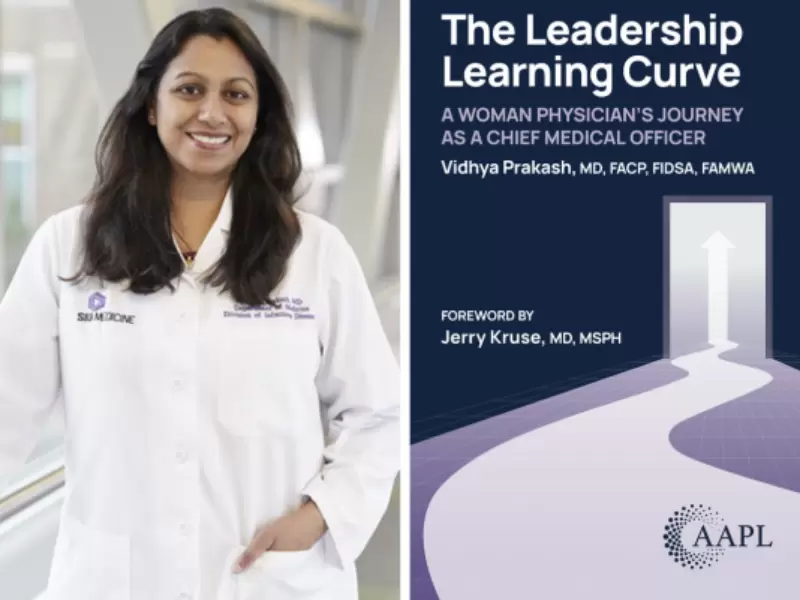

Indian diaspora leaders see their role as bridge builders, not lobbyists

At a webinar titled ‘Speaking up or Staying Quiet: Diaspora Perspectives on India and the United States’, organized by New India Abroad on Oct. 7, leaders acknowledged that while the diaspora’s emotional bond with India remains strong, its methods of engagement must evolve from sentiment to strategic, institutional advocacy — grounded in U.S. law and focused on shared national interests.

Poster of the webinar. / New India Abroad

Poster of the webinar. / New India Abroad

Amid renewed debate over the Indian diaspora’s silence in the face of recent U.S. policy actions affecting India, four prominent Indian-American leaders have urged the community to act with restraint, strategy, and integrity — not rhetoric — in advancing India–U.S. relations.

Speaking at a New India Abroad webinar titled 'Speaking up or Staying Quiet: Diaspora Perspectives on India and the United States', they said the diaspora’s role is not to lobby or protest on behalf of India, but to serve as a bridge of understanding between the world’s two largest democracies.

While reaffirming their deep ties to India, the speakers stressed that Indian-Americans must engage lawfully, institutionally, and as proud U.S. citizens — influencing policy through quiet diplomacy, civic participation, and credible advocacy rather than emotional or partisan appeals.

Responding to Criticism and Misperceptions

A sharp debate over the role of the Indian diaspora in shaping U.S. policy toward India has reignited after Indian parliamentarian Shashi Tharoor publicly wondered why the influential Indian-American community had remained “silent spectators” when the Trump administration imposed a $100,000 H-1B visa renewal fee and punitive tariffs on Indian goods.

The remarks, which went viral in both countries, questioned whether the five-million-strong diaspora had grown too comfortable to speak up for India’s interests. The controversy set the stage for a webinar, where leading Indian-American voices responded to the criticism and reflected on the community’s evolving role in bilateral relations.

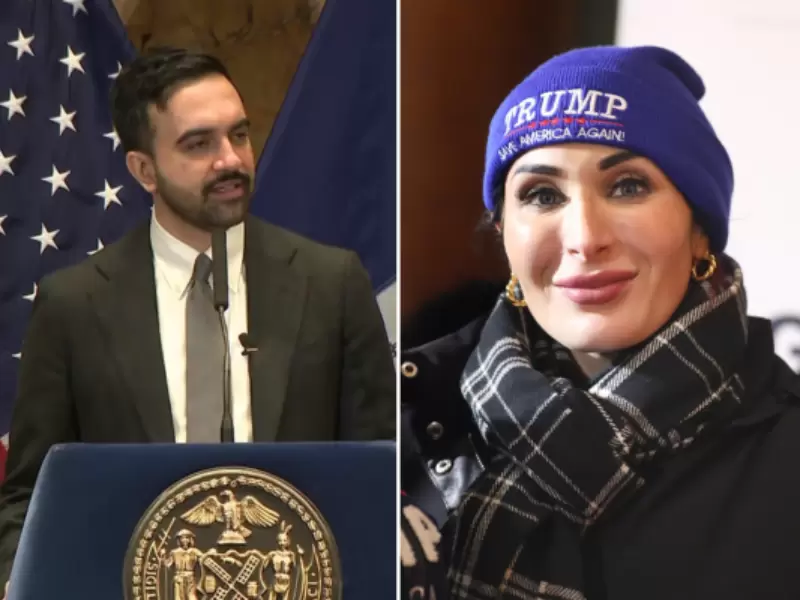

The webinar, moderated by journalist Rohit Sharma, brought together Ambassador (Retd.) Atul Keshap, President of the U.S.-India Business Council (USIBC); M.R. Rangaswami, Founder and Chairman of Indiaspora; Swadesh Chatterjee, Chairman of the U.S.-India Friendship Council; and Asha Jadeja Motwani, venture capitalist and founder of the Motwani Jadeja Foundation.

Across two hours of candid discussion, the speakers acknowledged that while the diaspora’s emotional bond with India remains strong, its methods of engagement must evolve from sentiment to strategic, institutional advocacy — grounded in U.S. law and focused on shared national interests.

Lawful Advocacy and Quiet Diplomacy

Ambassador (Retd.) Atul Keshap, President of the U.S.-India Business Council, said that diaspora activism should never cross the line into lobbying for a foreign government. “We live in a rules-based society,” he said. “Friends talk privately and respectfully, not by shouting from rooftops. The Indian-American community’s love for India is unquestionable, but our work must be lawful, thoughtful, and strategic.”

He emphasised that issues such as visa fees and trade tariffs were “driven largely by domestic political pressures in the U.S.” and not targeted against India, adding that the diaspora’s strength lay in “quiet, constructive diplomacy that builds trust rather than noise that breeds suspicion.”

Credibility, Contribution, and Civic Engagement

M.R. Rangaswami, founder and chairman of Indiaspora, agreed that the community’s influence came from credibility and contribution rather than confrontation. “We are just one percent of the U.S. population, but we pay six percent of its taxes,” he noted.

“Indian-Americans have already done a great deal — through remittances, technology, and social leadership. Our job is to educate, not agitate.” He said that while the diaspora naturally feels emotional about developments in India, “our engagement must always reflect American civic values — data, facts, and dialogue.”

Veteran community leader Swadesh Chatterjee, chairman of the U.S.-India Friendship Council, said the diaspora had in the past proved how effective it could be when it spoke the language of shared interests. “During the U.S.–India Civil Nuclear Deal, we didn’t say, ‘Do this for India,’” he recalled.

“We said, ‘This strengthens America’s energy security and global leadership.’ That’s what won bipartisan support.” He urged the community to sustain that approach through constant education of lawmakers and regular engagement on Capitol Hill, warning that “we cannot appear only when there’s a crisis.”

Venture capitalist and philanthropist Asha Jadeja Motwani argued that influence in Washington begins with participation. “Money opens doors in American politics — that’s how the system works,” she said candidly. “If we want to be heard, we must take part in political giving and policy discussions like every other community. The Jewish-American and Korean-American communities do it effectively; so can we.”

At the same time, she cautioned that the diaspora should focus on long-term relationship-building rather than reactive campaigns, saying, “Our goal should be to explain India, not to defend it.”

ALSO READ: Diaspora Diplomacy: Diwali Parties, Donations and Discussions on the Hill

Framing Issues in American Terms

Together, the speakers outlined a vision of a confident, law-abiding, and strategically engaged Indian-American community — one that acts as a bridge of trust between New Delhi and Washington.

They agreed that the diaspora’s future influence will depend not on emotional appeals or ethnic solidarity, but on professionalism, civic participation, and sustained institutional strength.

Opening the discussion, Ambassador Atul Keshap said criticism of the diaspora for its “silence” was misplaced. “The Indian-American community’s love for India is unquestionable,” he said. “But friendship between democracies also means respecting boundaries. It’s not about shouting from rooftops — it’s about talking quietly, constructively, and within the law.” He cautioned that diaspora activism must operate within the framework of the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA), which restricts lobbying on behalf of foreign governments.

“We live in a rules-based system. Advocacy has to be lawful, thoughtful, and strategic,” he said. Keshap added that the current irritants in India–U.S. ties — on trade, visas, and technology cooperation — are driven more by American domestic politics than by hostility toward India. “Issues like visa fees and tariffs stem from America’s internal job and manufacturing concerns. They’re not anti-India by design,” he said.

‘Living bridge’ between democracies

The ambassador described the diaspora as a “living bridge” between two democracies, arguing that its most effective role lies in building institutional and interpersonal trust, not in taking to the streets or issuing open letters. “Quiet diplomacy achieves more than loud gestures,” he remarked.

M.R. Rangaswami pushed back gently against the charge of diaspora apathy. “Let’s not forget what this community has already done,” he said. “Indian-Americans make up just one percent of the U.S. population, yet contribute six percent of its federal tax revenues.” He highlighted that Indian-origin doctors number around 75,000 in the United States, treating nearly 30 million patients annually, while Indian-American entrepreneurs run hundreds of technology companies that employ tens of thousands globally.

“Last year alone, India received $135 billion in remittances — about $30 billion of that came from the U.S. diaspora,” he said. “If that’s apathy, I don’t know what activism looks like.” Rangaswami argued that the diaspora’s influence operates not through protests or petitions but through economic and civic participation. “Our strength is in credibility — in being seen as contributing citizens. When we engage, we must do so as Americans of Indian origin, not as Indians lobbying the U.S. government.”

He also addressed the rising number of anti-India narratives and misinformation on social media. “Instead of reacting emotionally, we should educate and inform,” he said. “Indiaspora has been working to highlight data and facts that show India’s progress and its democratic values. That’s the responsible way to shape perceptions.”

Swadesh Chatterjee, who played a key role in securing congressional support for the 2008 U.S.–India Civil Nuclear Agreement, reminded the audience that the diaspora has historically risen to the occasion when it mattered most. “When the nuclear deal was stuck in Congress, it was Indian-Americans who went office to office, explaining why it was good for the United States,” he recalled. “We didn’t go in saying ‘Do this for India.’ We said, ‘This strengthens America’s global partnerships and energy security.’ That made the difference.”

Chatterjee said effective diaspora advocacy must always be framed in American terms, because U.S. lawmakers respond to what benefits their constituents and national interests. He also called for a more coordinated and bipartisan approach in Washington. “We need a structured mechanism — regular briefings, outreach to congressional staff, and a sustained presence on Capitol Hill,” he said. “We can’t appear only when there’s a crisis.”

Not lobbyists, bridge-builders

Responding to Tharoor’s comments, Chatterjee said the Indian diaspora’s silence should not be mistaken for indifference. “…I think the most important part of it, we are American. We are American of Indian origin. Let us not forget that, because we are out of India…But India is never out of us. But we had to go U.S. (and) India….we will explain that what diaspora can do and what they can do to influence but one thing we are not the lobbyist for government of India. We were never lobbyist for nuclear industry.” He meant the diaspora members are bridge-builders between two democracies, their job is to strengthen understanding, not to inflame tensions.

Asha Jadeja Motwani, who has been active in Silicon Valley and U.S. political circles, offered an unusually frank insight into how power and influence actually work in Washington. “Let’s be honest — in America, political engagement often starts with financial participation,” she said. “Writing a check or hosting a fundraiser gets you a seat at the table. Once you’re inside the room, you can make your case directly.”

Motwani said she had personally supported the Senate Leadership Fund and met with senior Republican lawmakers, such as Sen. Lindsey Graham and Sen. J.D. Vance, through that channel. “They were eager to hear about India, about its economy and technology sector,” she said. “But you only get that access when you participate in the system.” She urged the Indian-American community to shed its hesitation about making political donations and engaging in active campaigning. “Other ethnic groups — Jewish-Americans, Irish-Americans, Korean-Americans — have built strong political voices by engaging both parties. We need to do the same, and do it strategically.”

Motwani added that the Indian government could also benefit from professional public relations and policy outreach in Washington. “India’s story is powerful — but it needs to be told consistently, through experts who understand the American media and policy landscape,” she said.

Building Long-Term Institutional Strength

Throughout the discussion, the speakers agreed that the next phase of diaspora influence must rest on institutional strength, not personal networks or episodic activism.

Ambassador Keshap noted that the Jewish-American community had built think tanks and advocacy groups that have become respected, long-term players in U.S. policymaking. “They don’t just react to events — they shape them through scholarship, outreach, and continuity,” he said. “Indian-Americans need to invest in similar institutions that reflect American values while understanding India’s realities.”

Rangaswami concurred, pointing out that most members of the U.S. Congress have never visited India. “In contrast, every new member of Congress visits Israel as part of orientation. That’s how awareness is built,” he said. “We should create bipartisan delegations that experience India first-hand — its innovation, diversity, and democratic energy.”

Chatterjee added that Indo-U.S. friendship must be sustained by a permanent policy infrastructure, not just goodwill. “We need forums that bring together lawmakers, business leaders, and academics regularly — not just at crises or during prime ministerial visits,” he said.

Informed, sustained engagement needed

As the discussion drew to a close, the speakers were united in optimism about the long-term trajectory of India–U.S. relations, despite periodic friction over trade, technology, and human rights narratives. “India doesn’t need to be sold in Washington anymore,” Chatterjee said. “There’s bipartisan understanding that India is a democratic partner and a counterweight in the Indo-Pacific. What we need now is informed, sustained engagement to keep the relationship on track.”

Ambassador Keshap echoed that sentiment, emphasizing that India and the United States share a deep, resilient partnership built on values and people. “Governments will have differences — that’s natural between democracies,” he said. “But our people-to-people ties, our shared values, and our economic interdependence make this one of the most consequential relationships in the world.”

The panel agreed that the diaspora should not view itself as a lobby for India, but rather as a bridge between two democracies whose interests are increasingly converging. Rangaswami summed it up succinctly: “We’re not agents of India, nor critics of America. We are Americans of Indian origin working for what’s good for both nations. When those interests align — and they usually do — that’s when we’re most effective.”

Motwani added a final note of self-reflection: “Maybe we’ve been too comfortable, too proud of our success stories. It’s time to translate that success into civic participation — in politics, media, and policy. That’s how influence is exercised in a democracy.”

The webinar’s overarching message was clear: The Indian diaspora has moved beyond symbolic pride to strategic engagement. While Dr. Tharoor’s criticism may have stung, it also sparked an overdue conversation about how one of the world’s most successful immigrant communities can mature into a permanent stakeholder in global policy.

As one participant put it: “Our silence isn’t apathy — it’s restraint. Our activism isn’t about lobbying — it’s about partnership. The Indian diaspora’s role is not to echo governments, but to build understanding between two great democracies.”

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

E Paper

Video

1759953093.png) Staff Reporter

Staff Reporter

Comments

Start the conversation

Become a member of New India Abroad to start commenting.

Sign Up Now

Already have an account? Login