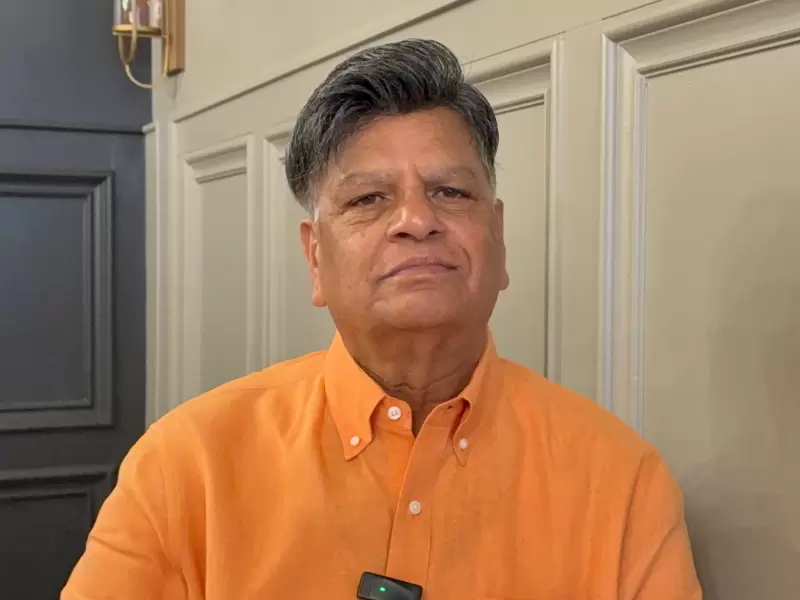

From small imports to a $150 million empire: The Houston journey of Jugal Malani

From modest beginnings as a small-time importer, Jugal Malani built a $150 million business while shaping Houston’s Indian-American community and giving back through philanthropy

Jugal Malani / Courtesy: Lalit K Jha

Jugal Malani / Courtesy: Lalit K Jha

When Jugal Malani first landed in the United States in 1979, the trip lasted barely three weeks. “I didn’t like it at all,” he recalled with a grin. The food was strange, the loneliness heavy. He returned to India, determined to stay put.

His wife, Raj, thought otherwise. “She told me, ‘You have to do something better than what you’re doing here,’” he said. At her insistence—and a second invitation from her brother and sister-in-law in America—he returned. What began as a reluctant experiment became a life’s work, one that mirrors the Indian-American ascent itself.

Also Read: Indian-origin scientist identifies immune cells linked to chronic inflammation and aging

An engineer turns entrepreneur

Trained as an engineer in India, Malani worked for several years before joining his in-laws in Houston in the early 1980s. He spent seventeen years with a local industrial firm before deciding, at midlife, to start his own venture.

“In 1997, we began with just two people—myself and my business partner,” he said. “By God’s grace, it expanded.” The company imported and distributed industrial products, eventually employing 150 people and generating about $150 million in revenue. Over the years, he bought and sold smaller firms, diversifying into complementary trades.

Today, the business is mainly in family hands. His son has been with the company for seventeen years and now serves as chief executive. The elder Malani still runs a smaller firm “to keep myself busy,” he said. “I’m already 72, so I’m slowly moving toward retirement.”

Houston’s transformation

When he first arrived, Houston’s Indian community was a fraction of its current size. “In 1979 or 1980, there was just one Indian restaurant—Taj Mahal on Highway 45—and maybe another called Bombay Palace,” he said. “Only one or two grocery stores, too.”

Now, he said, “Houston feels like mini-India.” The Hillcroft Avenue corridor, officially renamed the Mahatma Gandhi District, is lined with jewelry shops, sari boutiques, sweet shops, and vegetarian cafés. “There are over 75 temples and a hundred community organizations,” Malani said. “What you miss is only your family. Otherwise, nothing from India.”

He remembers personally supervising shipments at the port. “Those days we had to go ourselves to make sure cargo was unloaded,” he said. “I would stop at the Taj Mahal after finishing. It was near the port.”

The energy connection

Houston’s energy economy drew the first wave of Indian professionals. “It’s called the energy capital of the world,” Malani said. “They needed engineers, and that’s where Indians found jobs.” His own business supplied valves and fittings to oil-field companies.

The professional footprint widened quickly. “Earlier, we knew only the motel industry,” he said. “Now Indians are everywhere—engineering, medicine, education, franchises, private equity. Even smaller companies have Indian CEOs.”

He points to the University of Houston’s recent growth under Renu Khator, an Indian-origin leader. “She has taken it to a different level altogether in the last decade,” he said admiringly.

Tariffs and trade shocks

Few policies have tested importers like the tariffs imposed under former President Donald Trump. “This was a big shock to the industry,” Malani said. “Suddenly, in one month, Trump said you have to pay 25 percent, 50 percent tariffs on products. It’s challenging to pass that on.”

Manufacturing alternatives, he said, were unrealistic. “The products we deal in cannot be made here easily. Even if you build a plant, it’ll take years and cost much more—even with 50 or 60 percent tariffs.”

He found a compromise. “Our suppliers absorbed some, we absorbed some, and the rest went to customers. Everyone had a soft landing.”

He estimates the impact is split roughly three ways—about 30 percent each for suppliers, importers, and consumers, varying by product.

“Fortunately, our customers understood,” he said. “They knew it’s not us—the money goes to the government. The business is stable, with margins that are okay. In six months, people will forget about tariffs. New rates become the new rates.”

India in the crossfire

For importers of Indian goods, the tariffs added another layer of complexity. “Trump imposed around 40 percent on Indian products,” Malani said. “That hits both manufacturers and U.S. distributors.”

Every day, consumers notice it first. “Take Parle-G or glucose biscuits—they come from India,” he said. “Distributors share some of the tariff, suppliers help a bit, and the rest reaches the shelf.”

He expects delayed inflation. “Not immediate,” he said. “But six to nine months later, it shows in prices.”

Initially, many Indian-American business owners had welcomed Trump’s return, hoping friendlier ties would divert trade from China to India. “We thought India would be in the driving seat,” Malani said. “But it didn’t happen. Suddenly, high tariffs on India—it was a shock.”

He still hopes revisions are possible. “If final decisions bring India to 15–20 percent tariffs, that’s reasonable,” he said.

A call for selectivity

Asked what advice he would give to policymakers, Malani replied, “They shouldn’t put tariffs across the board. Some products simply can’t be manufactured here. Leave those alone. Where production is feasible, sure, encourage it.”

He rejects the notion that every import poses a threat to national security. “Garments, for example, aren’t national security,” he said. “They help poorer countries like Bangladesh and India, creating thousands of jobs. Those should not face high tariffs.”

Cost, he insisted, is the real limiter. “Labor here is expensive. Small-batch engineering items—one or two thousand pieces—can’t be made competitively in the U.S. Large-scale manufacturing, yes; small-scale, no.”

India’s manufacturing pivot

If tariffs prompted companies to reassess their sourcing strategies, India was poised to reap the benefits. “Earlier, 80 percent of our products came from China,” Malani said. “Any inquiry, we’d send it to China. They could do anything.”

That changed about five years ago. “Now we’ve found excellent factories in India—run by people who studied in the U.S., who understand communication and delivery,” he said. “Only 20 percent comes from China now; the rest is from India.”

His relatives have done the same. “My brother-in-law had a plant in China. He shifted it to India,” he said.

Emotion played a role, but economics ruled. “Of course, we feel attached,” he said. “But business doesn’t run on emotion. India can now compete with China. That’s why we moved.”

Ease of doing business

After decades of cross-border trade, Malani finds the U.S. system refreshingly straightforward. “Doing business here is simple,” he said. “No discrimination, no corruption. If your price, quality, and delivery are good, anyone will buy from you.”

India, by contrast, still demands navigation. “My family there faces hurdles,” he said. “You have to know people. It’s getting better, but not easy.”

Would he start a venture in India now? “No,” he said, smiling. “At this age, I’ll stay here.”

Learning to give back

Charity, for Malani, began at home—specifically, the home of his mentor, Ramesh Bhutada. “I lived with him when I first came here,” he said. “Even paying taxes was hard for me. He explained why—‘If you live in a community, you must give back.’ ”

Bhota’s example stayed. “He did a lot of charity work. That influenced me,” Malani said. “You see your friends doing good, and you start doing the same.”

He now supports a roster of organizations: Ekal Vidyalaya, India House, Hindu American Charities (HAM), Magic Bus International, and several temples. “A little bit everywhere,” he said.

Passing the baton

Like many first-generation immigrants, Malani measures success by what the next generation carries forward. “Right now, they’re not very involved in charity—they’re building careers,” he said. “But once they have children, they’ll change.”

He offers his own family as an example. “My son Pun and my nephews now take their kids to Chinmaya Mission to learn our Hindu ways,” he said. “I was president of India House; now my son is president. His son, my friends’ sons—they’re all getting involved.”

The continuity reassures him. “The younger generation is brilliant,” he said. “They’ve done better than us. They’ll see the importance of giving back.”

A broader legacy

After more than four decades in Houston, Malani embodies the arc of the Indian-American story: arrival, adaptation, enterprise, and philanthropy. He has watched the city’s skyline—and its diaspora—rise together.

He began as an immigrant engineer searching for a footing. He became a builder of companies, an employer, and a benefactor. And in the process, Houston itself transformed—from a city with two Indian restaurants into a cultural hub whose streets bear the name of Mahatma Gandhi.

“When I walk through Hillcroft now,” he said softly, “it feels like I’m in India. What I miss is only family.”

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

E Paper

Video

Lalit K Jha (IANS)

Lalit K Jha (IANS)

Comments

Start the conversation

Become a member of New India Abroad to start commenting.

Sign Up Now

Already have an account? Login