Understanding the Carnegie Indian American survey - The Hindu View

Initial coverage of the survey highlighted the growing importance of the Indian vs the South Asian identity among the diaspora.

US and India flag / X @ashajadeja325

US and India flag / X @ashajadeja325

In July 2025, the Carnegie Endowment published “How Indian Americans Live: Results From the 2024 Indian American Attitudes Survey.” As one of the few initiatives exploring trends and concerns related to the Indian American community, the Carnegie surveys provide some useful snapshots into the state and evolution of the community. Like any survey, however, the details are important and we call out a few issues of pertinence to the Hindu American community.

Initial coverage of the survey highlighted the growing importance of the Indian vs the South Asian identity among the diaspora. This is certainly important and a validation of COHNA’s push against the growing trend in the media to ascribe a South Asian identity over a Hindu or Indian American one. But there are other important findings that also merit further exploration.

Carnegie survey / Carnegie

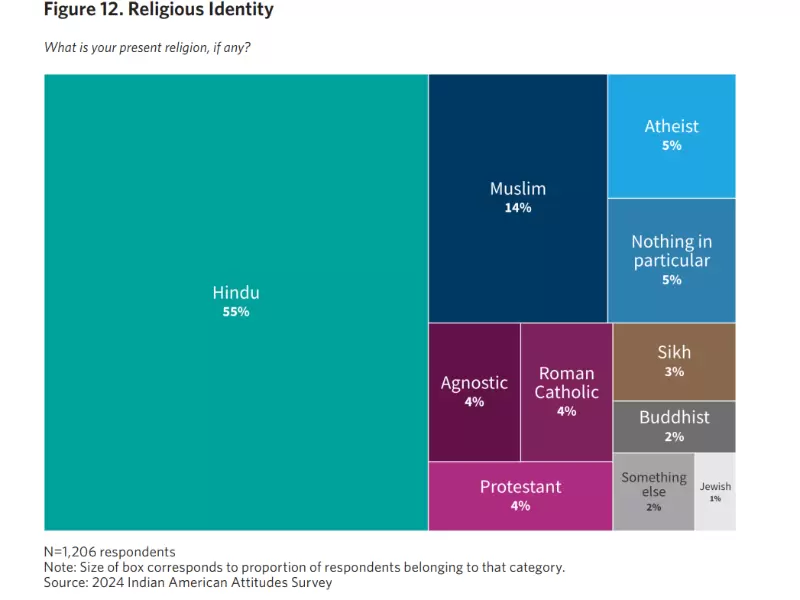

Carnegie survey / CarnegieHindu Americans Comprise Just about Half of Survey Respondents

In understanding the data, one important takeaway is that only 55 percent of Indian American respondents in the survey identify as Hindu, compared to nearly 80 percent in India. So there needs to be caution in projecting the takeaways from this survey onto the Hindu community as whole, since “Indian American” is often treated in the public imagination—and in policymaking—as synonymous with “Hindu American.”

This conflation has serious consequences. Non-Hindu Indian Americans are frequently elevated as the spokespeople for the entire community, even on issues that directly affect Hindus. When anti-Hindu legislation or bias emerges, such as the policies and legislation regarding caste, the wider Indian American community may not see it as a problem because it does not affect them. The result is that Hindus, even as the single largest group within the Indian American diaspora, are sidelined and misrepresented in discussions that touch directly on their faith and community.

This gap is particularly dangerous given that Hindus face real discrimination in the United States, from temple vandalism to stereotyping in schools. Yet their concerns are often minimized because “Indian American” leadership is not always synonymous with “Hindu American” leadership. Recognizing this distinction is vital to ensuring Hindu voices are not drowned out or spoken over within the broader Indian American umbrella.

Carnegie survey / Carnegie

Carnegie survey / Carnegie

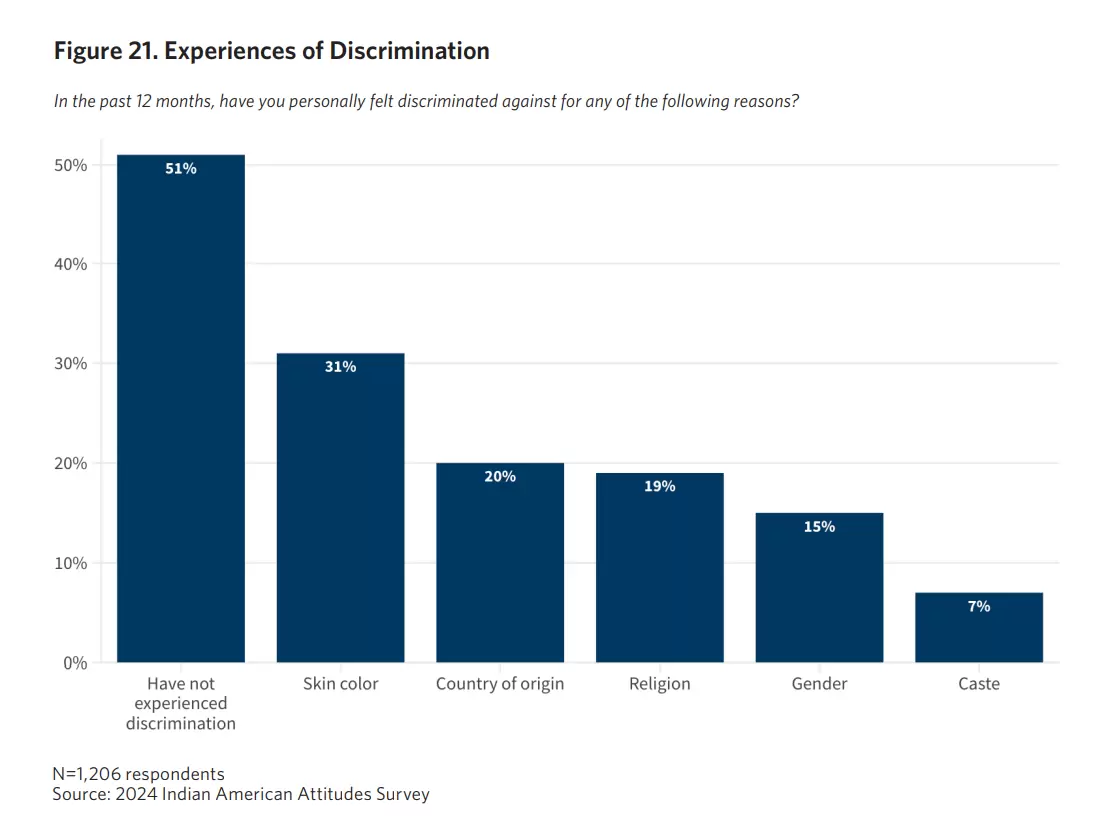

Caste Bogey and “Caste Discrimination” Policies

One of the most striking findings in the survey is that only seven percent of Indian Americans reported caste discrimination in the past year. By contrast, far higher shares reported discrimination on the basis of skin color (31 percent), country of origin (20 percent), or religion (19 percent). This confirms what CoHNA and other Hindu advocacy groups have consistently said: caste discrimination is not a widespread reality in the U.S., and existing anti-discrimination laws are more than sufficient to address any incidents that do occur.

And yet, the survey then asks respondents whether they support laws banning caste discrimination. Predictably, 77 percent say yes. But this is a loaded question, similar to asking, “Do you support genocide?” Few people are going to say yes.

The way the question is posed, itself generates a narrative of broad support for anti-caste laws, even though the data shows caste bias is hardly an issue compared to other forms of discrimination. Why did Carnegie choose to elevate the least occurring form of discrimination into a specific question asking for action?

The danger of such choices is clear: the questions themselves create a perception of a problem, which in turn would require special laws. It is important to remember that caste is not a neutral world, but one seen as a uniquely Hindu issue by leading dictionaries, search engines, media and more. While all forms of bias are wrong and already illegal, the addition of caste as a special category only creates new grounds to stigmatize and police Hindu communities.

Additionally, research from Rutgers Social Perception Lab showed that prevailing language around caste training and discussions is itself fuelling hate and suspicion about the broader Hindu community. That finding, and data from Carnegie’s own survey, should serve as a reminder that we need better community education on the hidden risks of anti-caste legislation and conversations.

Carnegie survey / Carnegie

Carnegie survey / CarnegieDefining “Hindu Observance”

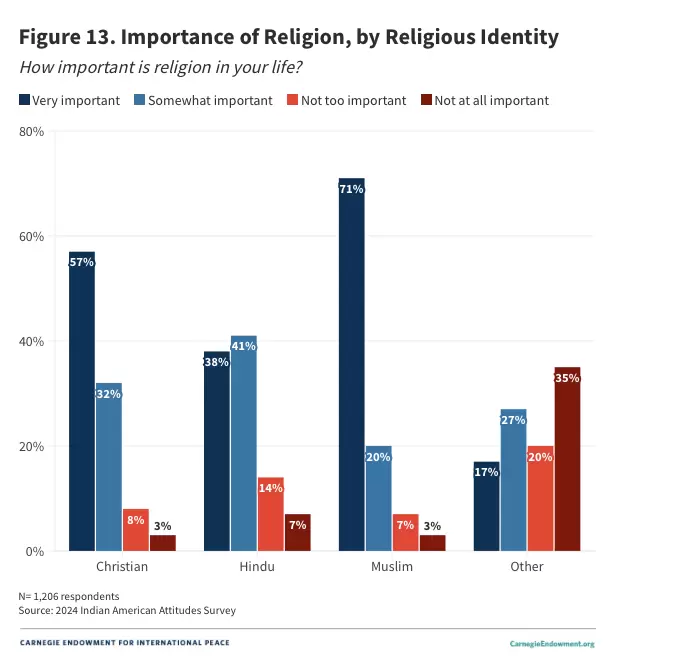

The Carnegie survey tries to measure religious observance by asking how often people attend religious services, apart from weddings and funerals. While this might be a reasonable approach when studying Abrahamic faiths, where weekly collective worship—Sunday mass, Friday prayers, Saturday services—is the norm, it does not translate well to Hindu traditions.

For many Hindus, daily practice happens in the home, through prayer, puja, meditation, or the observance of festivals. A family may go to the temple only occasionally—sometimes only once or twice a year—and yet still live deeply observant Hindu lives. Many Hindus also do not describe themselves as “religious” in the same way Christians or Muslims might, even though their religious practices are central to their identity.

The result is that questions like this tend to undercount or misrepresent Hindu religiosity. Rather than being a critique of the survey itself, this is an opportunity to explain a broader truth: Hindu and Dharmic ways of being do not always fit neatly into categories designed around Abrahamic norms. Understanding this difference is key to recognizing what it means to “be Hindu” in a society that often measures faith through non-Dharmic lenses.

Impact

Critics might also argue: “But this is a survey of Indian Americans, not Hindus—why does the distinction matter?” It matters because these findings are consistently used to speak for and about Hindus specifically. The survey’s framework is not neutral; it is built on assumptions drawn from other faith traditions, and Hindus are measured and judged by someone else’s yardstick.

The consequences are already here: caste legislation passed, Hindus seen as oppressive after DEI trainings etc. Each outcome was enabled by research that asked the wrong questions and elevated the answers into mandates for action.

In conclusion, the 2024 Carnegie survey captures important shifts in Indian American identity. But it also suffers from some fundamental flaws in the way it gathers data and the way its questions are framed that downplay the Hindu voice and create a false caste identity, even while strengthening a false narrative of caste discrimination. Hindu Americans remain misunderstood, miscounted, and misrepresented—even in research meant to illuminate their lives.

(The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of New India Abroad)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

E Paper

Video

Pushpita Prasad

Pushpita Prasad Mayuri Mukherjee-Pascar

Mayuri Mukherjee-Pascar

Comments

Start the conversation

Become a member of New India Abroad to start commenting.

Sign Up Now

Already have an account? Login