"When Gandhi and Mohammed Meet": Uniting through theatre in a divided world

Through interfaith romance, When Gandhi and Mohammed Meet excavates deeper questions.

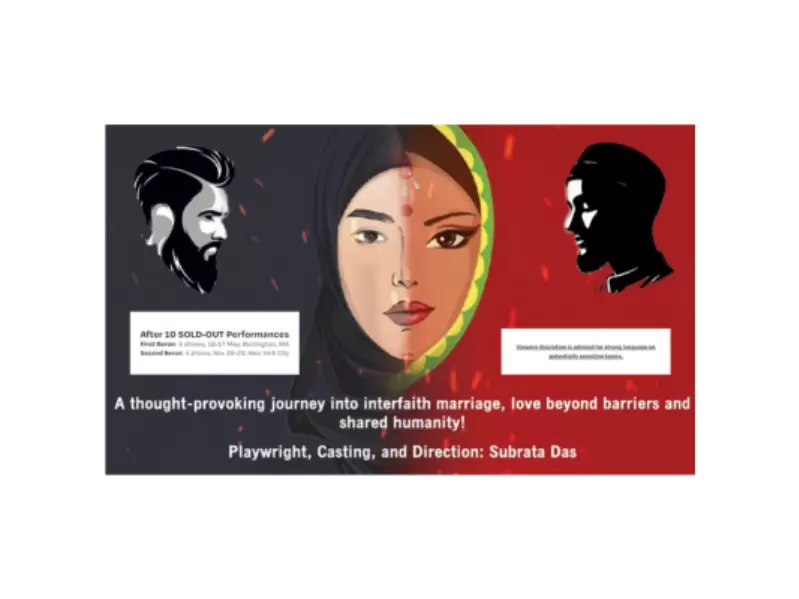

When Gandhi and Mohammed Meet—a bold, emotionally charged drama that dares to question the borders drawn by class, religion, and capital. / SETU

When Gandhi and Mohammed Meet—a bold, emotionally charged drama that dares to question the borders drawn by class, religion, and capital. / SETU

Theater is one of the few remaining democratic spaces where marginalized voices can speak—and be heard—without algorithmic interference or corporate dilution. Unlike sanitized media or curated digital platforms, live performance creates a shared space of vulnerability and resistance.

It allows communities to witness truth in real time, to feel what is often denied or dismissed, and to reclaim stories that have been silenced. For diasporic and working-class audiences, theater can be an act of cultural memory, a form of political education, and a spark for collective action.

When the forces of religion, nationalism, xenophobia, patriarchy and orthodoxy appear to be closing in on hard-won bastions of democracy, Boston-based theater collective Stage Ensemble Theater Unit (SETU) is using its platform to do what mainstream institutions ought to: speak truth to power.

Founded in 2003, SETU was born from a vision to uplift the marginalized, challenge the dominant narrative, and inspire the immigrant working class to embrace the cultural struggles that define their lived reality.

Co-founder and director Subrata Das, raised in a West Bengal village marked by Hindu-Muslim solidarity, channels those early memories of interfaith coexistence into When Gandhi and Mohammed Meet—a bold, emotionally charged drama that dares to question the borders drawn by class, religion, and capital.

After multiple sold-out shows in the greater Boston area, the ensemble is taking the show to Manhattan’s Gural Theater off-Broadway this fall. The cast is double-cast into two tracks—Belief and Faith—a conceptual nod to the dual narratives of division and unity the play interrogates.

The play, set across generations and continents, unfolds through the lives of two protagonists—Neel Gandhi, a London-based technologist, and Mohammed Aslam, a Delhi scientist.

Their bond, forged at an AI conference in Bangalore, grows from shared trauma: the fierce social and familial backlash they face for daring to love outside prescribed religious identities. But this is no star-crossed romance trope. It is an unflinching critique of how artificial lines—be they religious, cultural, or class-based—are enforced through violence, shame, and systemic exclusion.

“The play questions the architecture of separation,” Das notes. “Why are the intimate decisions of who we love and how we live policed by religious orthodoxy and cultural gatekeepers? This is about breaking inherited structures.”

Set in the hyper-modern domain of artificial intelligence—a field ostensibly untainted by religious dogma—the production draws a powerful contrast between the imagined neutrality of technology and the very real biases we embed into our institutions, data, and relationships.

It is a reminder that no system, not even one powered by code, is immune from the prejudices of its creators. As Shiv Sethi, who plays Neel reflects how “his character has assimilated, built a thick skin of resistance, but can’t escape who he really is.”

Intersectionality at Work

The cast and crew reflect SETU’s radical commitment to collective creativity and intersectional representation. From veteran performers to first-timers, they represent a cross-section of diasporic India: Hindu, Muslim, Christian, Dalit, upper caste, Bengali, Gujarati, Konkani, Punjabi, and more.

This isn’t diversity for optics—this is what solidarity looks like when it moves beyond tokenism and into practice.

For actors like Rimi Sarkar and Shabana Sayeed, who juggle dual roles with cultural nuance and emotional authenticity, the play demanded both technical skill and deep political awareness. “Comedy and tragedy operate on different frequencies,” Sarkar notes. “But both can expose hypocrisy and hold up a mirror to society.”

Others like Hamida Hirani-Merchant and Cini Kannan went further, grounding their performances in real-world ethnographic research—how working-class families dress, speak, age, and resist the erasure of their identities.

“I saw parts of my life in this role,” Hirani-Merchant shared. “That’s what makes it radical. We’re not just playing roles—we’re reclaiming stories we were told not to tell.”

The Politics of Performance

While much of American theater still panders to liberal nostalgia or hides behind “universal” themes that erase structural realities, SETU’s work brings up inequities and social injustice while remaining explicitly apolitical. And that’s what makes it powerful.

Through interfaith romance, When Gandhi and Mohammed Meet excavates deeper questions: Who defines legitimacy in love? Who benefits from communal hatred? And who suffers when the nation-state prioritizes identity over solidarity? “In the current environment, the topic of interfaith marriage, especially between Hindus and Muslims, looms large in India and for those living abroad,” says Dr Jayanti Bandyopadhyay, who is SETU’s co-founder and also plays the mother of one of the protagonists in the play.

The production’s minimalist staging is a rejection of capitalist excess, choosing instead to center the narrative, the actors, and the material conditions of their lives. Costume changes occur mid-scene. Families age 20 years in 10 minutes. This is not high budget Broadway polish—it’s radical theater in motion, proving that form can serve purpose.

Art as Resistance, Community as Power

SETU’s commitment to community theater goes beyond the stage. For performers like Manish Dhall, it’s “a lifeline, a claiming of space in a society that often renders immigrants invisible unless they conform to the model minority myth.”

“Community theater is about staying connected to each other and to our roots,” says Pranav Shukla. “It helps us question what we’ve been taught and move toward something freer, more just.”

Das affirms this ethos: “Social change is the long game, but it starts with awareness—challenging what we think is normal.”

You can catch the ensemble at Manhattan’s Gural Theater off-Broadway this November 20-23. For tickets and show information please visit SETU’s ticketing portal.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

E Paper

Video

Rahul Nair

Rahul Nair

Comments

Start the conversation

Become a member of New India Abroad to start commenting.

Sign Up Now

Already have an account? Login