BRICS 2026: Implications for a multipolar world

Today, BRICS accounts for nearly half of the world’s population and close to 40 percent of global GDP, comparable to the G7.

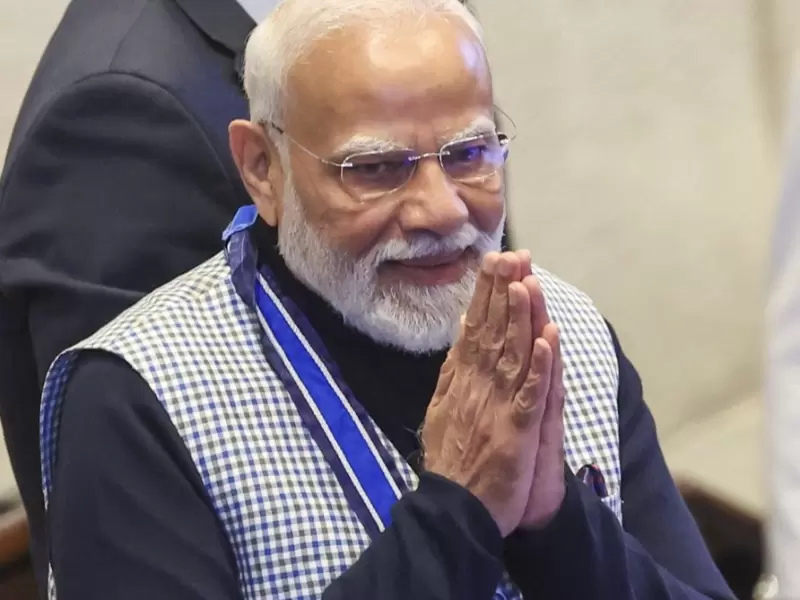

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi joins Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov, Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi Sheikh Khaled bin Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, Indonesian President Prabowo Subianto, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, Chinese Premier Li Qiang, Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, Egyptian Prime Minister Mostafa Madbouly and Iranian Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi for the family photo before the 17th BRICS Summit in Rio de Janeiro, B / IANS/PMO

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi joins Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov, Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi Sheikh Khaled bin Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, Indonesian President Prabowo Subianto, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, Chinese Premier Li Qiang, Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, Egyptian Prime Minister Mostafa Madbouly and Iranian Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi for the family photo before the 17th BRICS Summit in Rio de Janeiro, B / IANS/PMO

Recently, French Minister for Europe and Foreign Affairs Jean-Noël Barrot, while meeting India’s External Affairs Minister Dr S. Jaishankar, made an important observation. France, he noted, is heading the G7, in which India has been a permanent invitee for over a decade, while India will chair BRICS in 2026. As strategic partners committed to multilateralism, both countries see strong possibilities for cooperation in strengthening the global order.

President Emmanuel Macron reinforced this sentiment by stating: “India is going to be President of BRICS. I want to work with India to build bridges. BRICS countries must not become anti-G7, and G7 must not become anti-BRICS.” This reflects recognition of BRICS’ growing heft, the reality of an emerging multipolar world, and the need for collaboration rather than confrontation.

ALSO READ: Multiple U.S. States proclaim Jan 26

There is, indeed, convergence potential in an ideal scenario. The G7 continues to dominate global finance, technology, high value-added services, and controls major international institutions and currencies. BRICS, meanwhile, is increasingly a pivot for global growth, anchored in commodities, manufacturing, consumption, manpower, and vast markets, all of which are integral to global value chains. India–EU strategic partnership is set to deepen further with the signing of a trade agreement and the visit of EU leadership as Chief Guest for India’s Republic Day in 2026, a distinct honour underscoring the special relationship.

This perspective is especially significant at a time when unilateralism has become a dominant currency in international affairs. Recent examples include regime change in Venezuela and President Donald Trump’s withdrawal from 66 international agreements or organisations. The transatlantic alliance itself is under unprecedented stress. In this context, the desire to build cross-regional connections among mini- and plurilateral groupings is hardly surprising.

India, a founding member of both BRICS and the QUAD—often portrayed as being at opposite ends of the geopolitical spectrum—has consistently maintained that BRICS is not anti-West. Rather, it represents a non-Western alternative that articulates cross-continental aspirations of major economies from the Global South, including China and Russia as permanent members of the UN Security Council. With its inclusive worldview rooted in Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam—the world is one family—India is uniquely positioned to act as a credible bridge-builder across East–West and North–South divides.

Since US investment banker Jim O’Neill first coined the BRIC acronym for Brazil, Russia, India and China, the grouping has expanded to ten members, now including South Africa, Ethiopia, Egypt, Iran, Indonesia and the UAE. Saudi Arabia remains engaged and continues to participate in meetings, while Argentina, under a new pro-US political dispensation, opted out. At the Kazan Summit, the decision to introduce partner-country status reflected the strong interest of over two dozen nations eager to associate with BRICS, underlining its enhanced relevance in a disrupted world order.

Today, BRICS accounts for nearly half of the world’s population and close to 40 percent of global GDP, comparable to the G7. India, the world’s most populous country, brings exceptional human capital and is currently the fastest-growing major economy, having recently surpassed Japan to become the fourth-largest globally. BRICS countries collectively hold immense strength in energy production and consumption, critical minerals, and emerging technologies. Despite diverse political and economic systems, the grouping commands significant diplomatic weight due to its scale and mutual respect for national interests.

As Chair in 2026, India will host the BRICS Summit and a wide range of sectoral meetings covering commerce, connectivity, currency, counter-terrorism, culture, technology and fintech, education, R&D, traditional medicine, youth and sports exchanges. A central priority for both BRICS and India is the urgent need for reform of global institutions, particularly the UN and the UN Security Council, which risk irrelevance if they remain trapped in a post–World War II mindset dominated by the veto powers of the P5.

Under President Trump, driven by a strong MAGA constituency, the weaponisation of financial instruments has become a red line issue, with de-dollarisation viewed as unacceptable. The original BRICS members—Russia, China, India, Brazil and South Africa—have increasingly found themselves in Washington’s crosshairs, facing high and often unreasonable tariffs. This has only accelerated BRICS’ search for alternatives that avoid dominance and diktat, especially in the context of South–South cooperation.

While internal diversity can slow integration and complicate consensus, it also reinforces multipolarity by expanding options. Initiatives such as the New Development Bank offer alternatives to existing financial architectures. Discussions on a potential BRICS currency continue, though countries like India remain cautious. Nevertheless, unilateral sanctions and financial coercion have already pushed many nations toward greater use of national currencies in trade, a trend that could significantly reinforce multipolarity in the years ahead.

Multipolarity also implies decentralised security architectures. Within BRICS, Russia shapes Eurasian security dynamics, China dominates East Asian calculations, India asserts influence across South Asia, the Indian Ocean and the Global South, while Brazil and South Africa act as regional stabilisers. While this reduces global uniformity, it also heightens regional competition, sometimes increasing local instability.

Adding another layer of complexity, India is also slated to host the QUAD Summit in 2026 with the US, Japan and Australia. This presents a rare opportunity to address misperceptions, bridge gaps between perceived rival camps, and move beyond zero-sum thinking. Global challenges demand global solidarity.

BRICS is not seeking to replace the existing world order but to reshape it into a more collaborative, multipolar matrix. This process is already underway and will continue as long as powerful nations undermine the institutions they once created through unilateral approaches. India remains a voice of reason, advocating dialogue, diplomacy, and reform rather than wholesale replacement of global institutions.

India’s BRICS presidency in 2026 will reflect this approach, working to strengthen multipolarity and multilateralism at a time when both face serious threats. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has aptly redefined BRICS as Building Resilience and Innovation for Cooperation and Sustainability, while emphasising that condemning terrorism must be a principle, not a matter of convenience.

(Ambassador Anil Trigunayat is a former Indian Ambassador to Jordan, Libya and Malta, and currently a Distinguished Fellow with the Vivekananda International Foundation and the United Services Institution of India.)

(The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of New India Abroad.)

Discover more at NewIndiaAbroad

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

E Paper

Video

Anil Trigunayat

Anil Trigunayat

.jpg)

Comments

Start the conversation

Become a member of New India Abroad to start commenting.

Sign Up Now

Already have an account? Login