Bihar’s fractured mirror: glory, grit, and the ghosts of 2025

Bihar’s 2025 isn’t binary—backslide or rebound—but a mosaic. Upper castes, once unchallenged, now coalition crutches; backwards, empowered yet entangled.

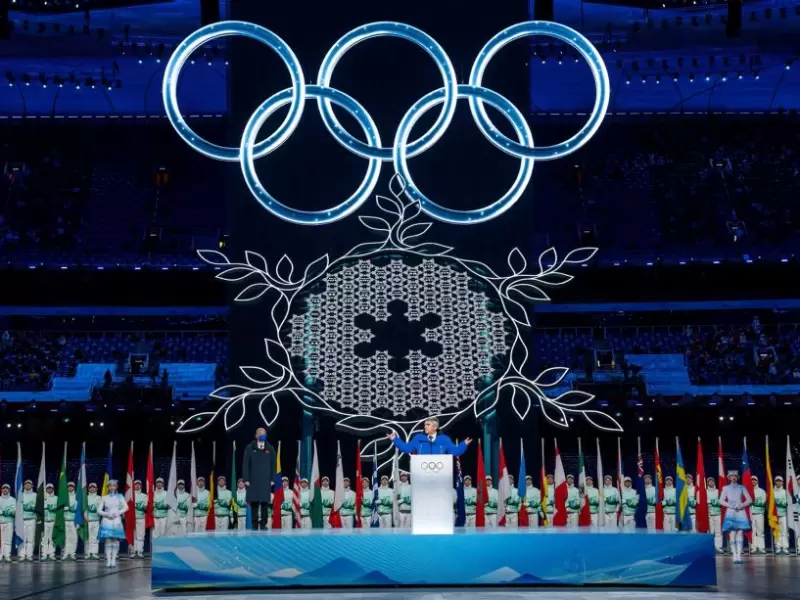

People at a election rally in Bihar. / X Via @NitishKumar

People at a election rally in Bihar. / X Via @NitishKumar

In the sweltering haze of a Patna afternoon, where the Ganges slithers like a half-forgotten promise, Bihar stares at its reflection in cracked glass.

Once the cradle of empires and enlightenment, today it’s India’s starkest paradox: a land that birthed democracy under ancient sanghas, yet grapples with a poverty so deep it mocks the marble memorials of Nalanda.

As the 2025 assembly polls loom—voting on November 6 and 11, results on the 14th—the state isn’t just electing leaders; it’s wrestling with its soul.

Will it cling to the inertia of coalitions stitched from caste threads, or shatter the mirror for a glimpse of something bolder? The stakes aren’t just political; they’re existential. Bihar, the mother of faiths and fortitude, deserves better than survival.

Let’s start with the unvarnished truth: Bihar is, unequivocally, India’s poorest state. In 2024-25, its per capita income hovers at a dismal ₹60,000—about $715 annually—lagging the national average of ₹1.7 lakh by a chasm wider than the Son River.

That’s not hyperbole; it’s ledger fact, etched in reports from the National Statistical Office and Reserve Bank of India. Half of Bihar’s 45,000 villages limp along on under $400 per capita yearly, per district-level data from the Bihar Economic Survey.

Floods ravage the north, droughts scorch the south, and infrastructure—those vaunted roads under Nitish Kumar—feels like a Band-Aid on a hemorrhage. Yet, amid this, there’s a quiet alchemy: Biharis are happy in their poverty, or at least resigned to it.

Enterprise flickers like a diya in the wind—small shops, cycle-rickshaws, the odd sattu vendor—but grand ambitions? Rare as a reliable monsoon. It’s a contentment born of endurance, not complacency; a folk wisdom that whispers, “Jo hai, so hai” (What is, is).

This isn’t defeatism; it’s defiance wrapped in nostalgia. Bihar’s pride swells from a past so luminous it casts long shadows over the present. Remember Bodh Gaya, where Siddhartha Gautama touched the earth in 5th century BCE and birthed Buddhism, a faith that wandered to Kyoto’s temples and Bangkok’s wats?

Or Vaishali, cradle of Jainism, where Mahavira preached ahimsa amid lotus ponds? Bihar nurtured Sikhism too—Guru Gobind Singh, the tenth guru, drew his first breath in Patna’s dust in 1666, his Takht Sri Patna Sahib a beacon for pilgrims.

And Hinduism? Sita, Rama’s eternal consort, emerged from Mithila’s soil in Sitamarhi, her janmabhumi a testament to the Ramayana’s roots.

These aren’t dusty footnotes; they’re veins pulsing through Bihar’s identity. The sense of faded glory isn’t arrogance—it’s armor. In village chaupals, elders recount Nalanda’s 10,000 scholars predating Oxford by centuries, a litany that steels the spirit against today’s ledgers of lack.

But glory’s echo rings hollow when contrasted with the diaspora it birthed. Bihar didn’t just export ideas; it exported its people—chained in girmitiya contracts by British overlords from the 1830s to 1917.

Over 1.5 million Bhojpuris, mostly from eastern Bihar’s Bhojpuri heartland, were shipped as indentured labor to sugarcane fields in Fiji, Papua New Guinea’s fringes, Mauritius’s cane belts, and the Caribbean’s sun-baked isles—Trinidad, Guyana, Suriname.

They went as slaves in all but name, duped by tales of El Dorado, enduring the kala pani’s crossing with little more than a tin trunk and a prayer. Yet, look at them now: descendants leading nations.

Mauritius’s four prime ministers since independence? All Bihari-rooted Indo-Mauritians. Fiji’s politics? Indo-Fijians, many Bhojpuri, shape coups and coalitions. In Trinidad, Basdeo Panday, son of a sugarcane cutter from Bihar’s veins, became the first Indo-Caribbean PM. Guyana’s Cheddi Jagan? Another Bihari echo in the corridors of power.

They fled famine and zamindari whips, only to till foreign soil into thrones. It’s Bihar’s ironic gift: a state too broke to keep its sons, yet seeding leaders abroad. Remittances flow back—$2.5 billion in 2024 alone—but the brain drain hollows the homeland. Why build here when Delhi or Dubai pays?

This exile traces an eight-decade slide, a freefall from British-era beacon to begging bowl. Under the Raj, Bihar was no backwater; it was the empire’s jewel in the east. Patna (then Patliputra) hummed with trade, its zamindars—Bhumihars, Rajputs, Kayasthas—bankrolling Calcutta’s mills.

Per capita income rivaled Bombay’s in 1901, fueled by indigo, opium, and rail hubs like Mughalsarai. The Permanent Settlement of 1793, Cornwallis’s zamindari fix, locked in feudal fiefdoms, but Bihar thrived as Bengal Presidency’s breadbasket.

Post-1947? Catastrophe. Partition carved Jharkhand’s minerals away in 2000, but the rot set earlier: freight equalization policies funneled Bihar’s coal and mica to coastal ports, starving local industry.

Congress’s socialist stutter—license raj, neglect—let roads crumble and factories rust. By the 1960s, growth flatlined at 2.5% annually, half the national clip. Lalu’s “Jungle Raj” (1990-2005) amplified the anarchy: kidnappings, fodder scams, a GDP per capita that dipped below sub-Saharan averages.

Nitish’s turnaround post-2005 juiced 10% growth, but it’s low-base math—poverty clings at 33.7%, highest in India. Bihar’s GSDP? A measly 3% of national pie, despite 9% of the population. It’s a tale of squandered potential: from Mauryan might to Mandal mess.

Enter the arena where this history bleeds into ballots: caste, Bihar’s eternal fault line. Politics here isn’t policy; it’s pedigree. From 1947-1967, upper castes—Kayasthas kickstarting with Sachchidanand Sinha’s interim ministry—held the fort.

For two decades post-Independence, Kayasthas (scribes turned satraps) like Shrikrishna Sinha and later Krishna Ballabh Sahay steered the Congress chariot, blending administrative savvy with zamindari clout.

Then, turbulence: the 1960s’ socialist stirrings birthed coalitions, but upper castes clung on. Brahmins and Thakurs (Rajputs) tag-teamed for another 20 years—Jagannath Mishra’s three stints (1975-90), a Brahmin dynasty of doles and riots; Karpoori Thakur’s brief Nai interlude (1977-79) sparking upper-caste backlash. Bindheshwari Dubey’s reign (1985-88) promised stability but drowned in fodder floods.

Upper castes—15% of the populace—hoarded 40% of assembly seats till 1990, their vote banks of docile Dalits and Muslims ensuring feudal fiefdoms. Reservations? Token. Development? For the few.

The quake came in 1990: Lalu Prasad Yadav’s Janata Dal tsunami, cresting on Mandal’s OBC wave. Upper castes? Routed. Bihar’s politics splintered along caste chasms—upper vs. shades of backward. Yadavs (14%), Kurmis (4%), Koeris (4%)—the upper OBCs—seized the scepter, their “MY” (Muslim-Yadav) math toppling the old guard.

Lower OBCs (EBCs, 36%) simmered, Dalits (19%) splintered. The BJP, upper-caste bastion, stormed the Hindi heartland—UP, MP, Rajasthan—but Bihar resisted. Why? Mandal’s roots run deeper here; Karpoori Thakur’s 26% quota (1978) was Bihar’s original sin for savarnas.

BJP forges coalitions—Nitish’s Kurmi clout, Chirag Paswan’s Dusadh Dalits—but solo majority? Elusive. In 2024 Lok Sabha, NDA swept on upper-OBC-Dalit arithmetic, but assembly’s 243 seats demand finer filigree.

Youth, Bihar’s perennial firebrand, fuels this fault line. From Gandhi’s 1917 Champaran satyagraha—indigo peasants marching under his banner—to JP Narayan’s 1974 student storm toppling Indira, the young have been agitators-in-chief.

JP, Bihar-born, galvanized campuses against corruption, birthing the 1977 Janata wave. Today’s twentysomethings? Overly political, underemployed—10.8% youth unemployment, per 2025 Economic Survey. They flood Gulf taxis, Delhi call centers, fueling ₹1.5 lakh crore in outward migration.

Polls pulse with their pulse: Tejashwi Yadav (35, Yadav) leads CM ratings at 42% (C-Voter, Oct 2025), his “10 lakh jobs” vow a siren song. But enter the wildcard: Samrat Choudhary, BJP’s upper-caste (Rajput) deputy CM, 52 but Bihar’s “young gun” in saffron drag. Approval? Sky-high at 38%, per Axis My India—edging Nitish’s 35%.

A Patna boy turned Patliputra strongman, Choudhary’s “Bihar First” rhetoric—anti-corruption drives, upper-caste consolidation—resonates. Yet, analysts (The Hindu, Oct 2025) peg him as NDA’s glue, not kingmaker. Unlikely to helm solo; coalitions rule.

Predictions? A nail-biter. IANS-Matrize (Oct 2025) gifts NDA 150-160 seats (49% vote), Mahagathbandhan 75-85 (38%), Jan Suraaj’s Prashant Kishor snagging 15-20 as spoiler.

Times Now-JVC echoes: NDA 136, BJP surging to 90 on upper-caste math. INDIA’s Tejashwi dreams of “Tejashwi Ka Pran” manifesto—jobs per household, free power—but caste census calls expose fractures.

NDA’s “elder brother” JD(U) (Nitish, 74, health wobbly) eyes 60 seats, BJP 100, Chirag 30, Manjhi 5. Yet, EBCs waver—36% bloc, kingmakers. SIR’s voter purge? 1.63 lakh added in Patna alone, but disenfranchisement whispers target MY. Backsliding? Or reversal via protests, courts, polls?

Bihar’s 2025 isn’t binary—backslide or rebound—but a mosaic. Upper castes, once unchallenged, now coalition crutches; backwards, empowered yet entangled.

Youth like Choudhary symbolize saffron’s savvy pivot: not dominance, but deal-making. But inertia looms—Nitish-Tejashwi redux, per Lokniti-CSDS. The diaspora lesson? Bihar builds abroad because home builds barriers. To break free: invest in skills, not slogans. Dredge the Ganges for industry, not just piety. Let Nalanda’s ghost guide: knowledge over kinship.

As polls peak, picture a young voter in Muzaffarpur, scrolling remittances from a cousin overseas. He marks his ballot not for caste, but cashflow. Bihar’s mirror might finally reflect wholeness—not glory’s ghost, but grit reborn. In this democracy’s cradle, the revolution could be quiet: a vote for venture, not vendetta. Jai Bihar—not just in verse, but in velocity.

The author co-founded the national Hindi daily Jansatta and was the chief editor of Dinamaan, the national newsweekly of The Times of India Group. Newspaper Subscriptions

(The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of New India Abroad.)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

E Paper

Video

Satish Jha

Satish Jha

Comments

Start the conversation

Become a member of New India Abroad to start commenting.

Sign Up Now

Already have an account? Login