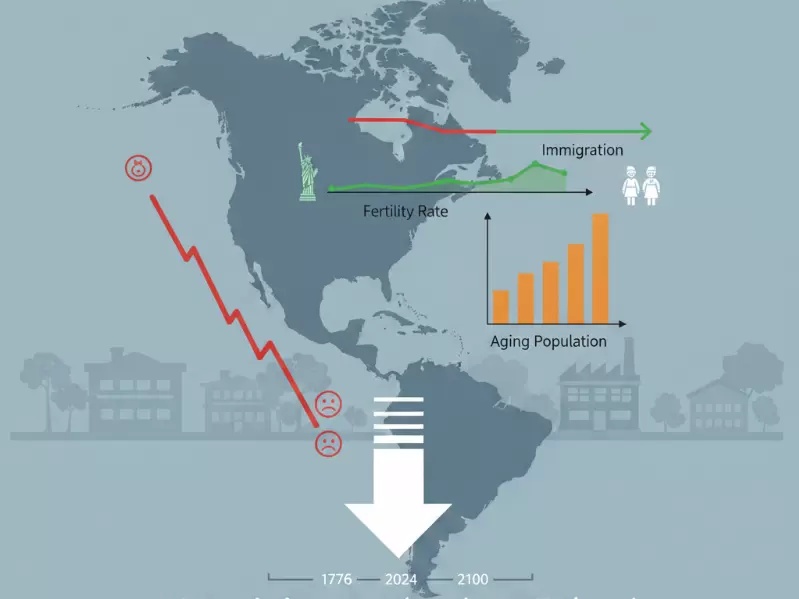

America’s incredibly shrinking population

Under lower immigration scenarios, the U.S. population could shrink as low as 226 million by the year 2100, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau.

Representative image / AI generated

Representative image / AI generated

The Trump administration has introduced policies to encourage Americans to have more children, most notably through the “Trump accounts” established by the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, which provides a $1,000 federal contribution for eligible newborns. The United States is edging toward population decline as birth rates fall, the population ages, and immigration slows, removing the country’s long-term demographic safety valve. At the American Community Media Weekly National briefing, panelists discussed the demographic engines that have powered America’s economic and geopolitical ascent since 1776 — fertility and immigration — that are faltering today.

Under lower immigration scenarios, the U.S. population could shrink as low as 226 million by the year 2100, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau. This trend mirrors a global shift already reshaping Europe and East Asia. Two-thirds of humanity lives in countries with fertility rates below the replacement rate of 2.1 children per family. By 2100, populations in some major economies will fall by 20% to 50%.

Factors leading to negative population growth

Population growth is shaped by four core forces — fertility, or the average number of children per woman; mortality; migration; and the age structure of a society — said Dr. Ana Langer, director of the Women and Health Initiative at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and professor emerita in the Department of Global Health and Population. Each of these operates within a broader context that includes economic development, education, women’s rights, health care access, family planning and public policy.

Among these determinants, fertility rates have shifted dramatically over the past half century. The trend is unmistakable and nearly universal. In 1970, women globally had an average of about five children. By 2024, that figure had fallen to roughly 2.2.

The regional patterns mirror broader population dynamics. Sub-Saharan Africa, still the region with the highest fertility, averages about 4.5 children per woman today, down substantially from previous decades. Asia, which experienced rapid population growth in the 1970s with fertility rates near five, now sits at approximately 2.1, around replacement level. In Latin America and the Caribbean, fertility has fallen even further, from about 4.5 children per woman in the 1970s to 1.9 in 2024, below replacement. The United States follows the same trajectory, from roughly 3.5 children per woman in the 1960s to about 1.6 today.

What is causing this decline in fertility in America?

Multiple national surveys shed light on why Americans are having fewer children. Respondents who revised their ideal family size over time most often cited affordability concerns, negative experiences with pregnancy or childbirth, and unease about the state of the world. The cost of child care looms especially large.

According to the Department of Labor, families spend up to 16% of their income on day care for a single child. Rising housing and food costs force many people to prioritize financial stability over parenthood. More than a quarter of survey respondents strongly agree that overpopulation and climate change make them uneasy about raising children on a planet under strain.

Among those who do not plan to have children at all, simply not wanting them is by far the most important reason, reflecting the growing acceptance of a child-free life. Persistent gender inequalities, both at home and in the workplace, continue to influence decisions to delay or forgo parenthood, Dr. Langer said. Higher levels of education and labor force participation among women, while profoundly positive developments, also mean later family formation and heightened concerns about work-life balance.

At the same time, unintended pregnancies in the U.S. have declined significantly, reaching record lows in 2024, largely due to improved sex education and access to contraception.

What is causing this decline in fertility in China?

China offers a particularly revealing case study, both because of the scale and duration of its population policies and because of the quality of the demographic data it collects, said Dr. Langer. Alarmed by rapid population growth, the Chinese government introduced the one-child policy in 1979, enforcing it nationwide until 2015. By the time the policy took effect, fertility was already in decline. During the 1970s, births per woman fell from roughly five or six to about 2.7 by the end of the decade.

Under the one-child regime, China’s total fertility rate dropped well below replacement level. When population decline became a concern, authorities reversed course. In 2015, the government replaced the one-child rule with a two-child policy, followed by a three-child policy in 2021, in an effort to encourage larger families. Yet loosening restrictions failed to reverse the trend. Fertility continued to fall, reaching an estimated 1.09 births per woman in 2022, among the lowest rates recorded anywhere in the world.

The end of the one-child policy did not bring fertility back to replacement levels. Deeply rooted cultural and economic pressures, including high living costs, intense career demands and delayed marriage, have kept birth rates stubbornly low.

The Chinese government introduced a broad package of pronatalist measures designed to make childbearing more economically and socially feasible. These include direct financial incentives, tax and social insurance benefits, expanded child care and education support, housing subsidies, workplace protections aimed at improving work-life balance, and increased access to health care and fertility services.

So far, the impact has been limited.

Are the Trump administration’s incentives working?

Incentives alone are often insufficient to overcome the structural forces driving fertility decline, said Dr. Langer.

An Associated Press-NORC poll confirmed that few U.S. adults prioritize increasing the birth rate. Instead, Americans are more likely to want the government to focus on improving health outcomes for pregnant women and reducing child care costs.

What is striking about declining fertility is how universal the trend has become, said Anu Madgavkar, a partner at the McKinsey Global Institute. Countries start at different levels and fall to different endpoints, but once fertility drops below replacement, there is little evidence that it can be sustainably reversed.

The age structure and population size are setting the stage for major economic transformation

Most countries now face a dual demographic shift: fewer young people, many more older adults, and in many cases a stabilizing or shrinking total population. Both the age structure and the overall population size matter, and together they are setting the stage for major economic transformation, Madgavkar said.

As the share of people ages 15 to 64 — the core working-age population — shrinks, growth in per capita GDP slows as well.

Older adults continue to consume even as they exit the labor force. The gap between what seniors consume and what they earn, the so-called “senior gap,” is largely funded through public transfers such as Social Security. In the U.S., about half of that gap is covered through transfers; in parts of Europe, it can be as high as 80 percent.

If current trends persist, that gap is projected to rise by roughly 10 percentage points of total labor income, effectively the equivalent of an additional tax burden on workers. Because Social Security accounts for a large share of these transfers, the fiscal strain will intensify.

Aging populations will require either higher taxes, reduced benefits or faster productivity growth.

Automation and AI may help absorb some of the shock. More than half of all work hours in the U.S. economy have the technical potential to be automated, whether through digital AI systems or robotics. Success will depend on large-scale reskilling, not workforce replacement.

Historically, larger families provided economic and caregiving security, especially during crises. Smaller families raise new questions about how care, aging and intergenerational responsibility will be managed.

As family size shrinks, social contracts will evolve. Aging in place, new care models and shifts in public versus private responsibility are all likely. Ultimately, these choices hinge on economic capacity. If societies generate sufficient resources through productivity and growth, they can redesign social systems to support both older and younger generations.

The reality is that even if fertility were to rise tomorrow, it would not meaningfully expand the workforce for two decades or more. Immigration, while important, cannot close the gap on its own; in many countries, inflows would need to multiply several times over to offset aging, a scale that would be difficult to absorb.

In the near term, adaptation, not reversal, is unavoidable. Demographic change is already locked in for the next 20 to 25 years. The challenge for policymakers is not how to restore the past, but how to build economies and social systems that function in a world with fewer births, longer lives and a fundamentally different population structure.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

E Paper

Video

Ritu Marwah

Ritu Marwah

Comments

Start the conversation

Become a member of New India Abroad to start commenting.

Sign Up Now

Already have an account? Login