How the Trump Administration Is Reclassifying Lawful Immigrants as “Unauthorized”

The Justice Action Center is leading multiple lawsuits against the administration’s immigration policies, arguing that recent actions unlawfully strip legal status from immigrants

FILE PHOTO: Male migrants from Jordan, China, Egypt and Colombia surrender to a border patrol agent after crossing into the U.S. from Mexico in Jacumba Hot Springs, California, U.S., May 15, 2024. / REUTERS/Adrees Latif

FILE PHOTO: Male migrants from Jordan, China, Egypt and Colombia surrender to a border patrol agent after crossing into the U.S. from Mexico in Jacumba Hot Springs, California, U.S., May 15, 2024. / REUTERS/Adrees Latif

What happens to my children if I lose my work permit? Should I stop driving for fear of being pulled over? Is it safer to move or to disappear? What happens to my U.S.-born children if I’m detained? These are real questions that haunt families as they go about their workdays.

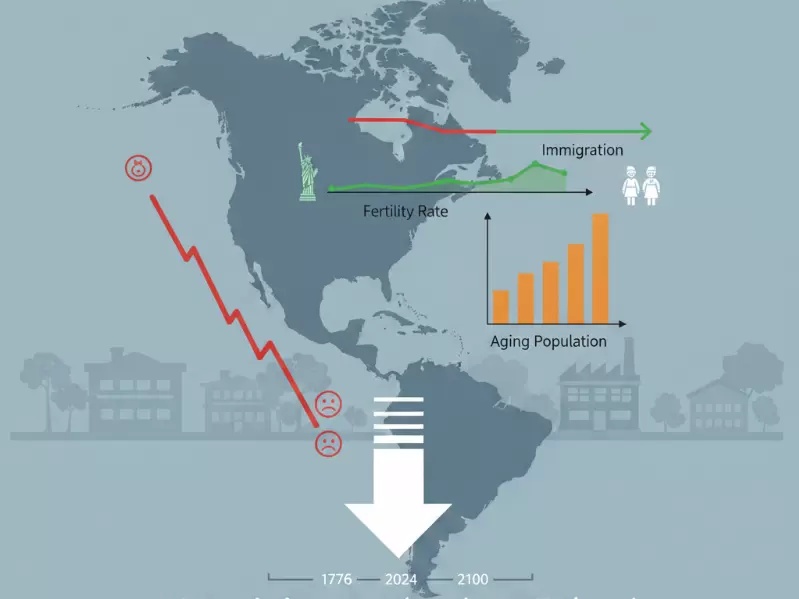

American Community Media weekly national briefing examined the profound shift in the U.S. Immigration policy. How the Trump administration is taking groups of immigrants who have lived here legally, some for years or decades and finding a way to reclassify them as unauthorized, or taking away status from people.

“Our families feel like political bargaining chips. One day we’re welcome. The next day we’re disposable,” said Laura Flores-Perilla, an attorney at the Justice Action Center.

Lawful Immigration at Risk

U.S. immigration law recognizes far more than just citizenship and green cards, but many of those lawful statuses are now being targeted by the current administration, said Hiroshi Motomura, Co-Director, UCLA Center for Immigration Law and Policy.

“The first thing to understand is that U.S. law recognizes many different lawful immigration statuses,” Motomura said. In addition to citizenship and lawful permanent residence, the system includes numerous interim legal categories that allow people to live and work in the United States while pursuing long-term status.

“These are not long-term statuses, but they come with work permits, and they are definitely lawful,” he said. Many people in these categories are already applying for green cards or other durable legal status.

Among them are Temporary Protected Status (TPS), a humanitarian designation for people from countries facing war or natural disaster; humanitarian parole, which grants permission to remain in the country; and Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA). Motomura said these lawful statuses have become the focus of the administration’s immigration crackdown through expiration, rescission, or termination.

The administration has also announced plans to reexamine permanent legal status that has already been granted, including green cards issued through asylum and refugee pathways.

“People who believed they were securely on a path to permanent residence are now being told that status itself may be reconsidered,” Motomura said.

Even citizenship, long considered the most secure legal status, may no longer be immune. Motomura warned that the administration has expressed strong interest in denaturalization, revoking citizenship from naturalized Americans by reopening past cases.

At the same time, a 2025 executive order seeks to redefine who qualifies as a U.S. citizen. Traditionally, citizenship has been granted to anyone born on U.S. soil. Under the proposed framework, citizenship would require that at least one parent be a U.S. citizen or lawful permanent resident.

Although the administration has said the policy would apply only going forward, Motomura cautioned that the order’s language could redefine citizenship more broadly.

“If approved, that would take citizenship away from many people who already have it,” he said.

Immigration enforcement intensified further following a violent incident involving an Afghan refugee in Washington, D.C. Soon after, the administration announced the suspension of immigration processing for people from 19 countries, halting green card applications and other legal pathways.

“The immediate effect is that processes people are legally entitled to are being stopped,” Motomura said. While the administration has justified the move on national security grounds, he said aspects of the policy raise serious concerns about religious and racial discrimination and are likely to be challenged in court.

Beyond the legal consequences, Motomura emphasized the broader climate of fear these actions have created. “The practical effect is much broader than the legal effect,” he said. “People stop applying. People are afraid to travel. People who qualify for citizenship are afraid to naturalize.”

In his view, the administration is drawing sharp lines around belonging. “Some people are being made to feel they belong, and others that they do not,” he said, describing an environment that discourages immigrants from speaking out or asserting their rights.

Historically, Motomura said, the U.S. immigration system has relied on a mix of narrow legal entry pathways and informal tolerance, while maintaining humanitarian and temporary legal protections for decades, dating back at least to World War II.

“What’s unprecedented now is the intensity,” he said. “This administration is going after people who already have lawful status.”

Motomura believes the broader goal is to reverse the post-1965 immigration framework, which sought to make the system more neutral. Instead, he sees an effort to return to an earlier era that favored European immigrants.

“It’s an attempt to turn back the clock,” he said, “as if the 20th century didn’t happen.”

Move to End Humanitarian Parole

The Justice Action Center is leading multiple lawsuits against the administration’s immigration policies, arguing that recent actions unlawfully strip legal status from immigrants who entered the United States through long-standing humanitarian programs.

Laura Flores-Perilla, an attorney at the Justice Action Center, said humanitarian parole has been used by administrations from both political parties for more than 70 years to provide safe, legal entry into the U.S. during humanitarian crises abroad. Parole recipients are also granted authorization to work.

“Parole is a lawful pathway that has existed for decades,” Flores-Perilla said. She pointed to programs such as Uniting for Ukraine, Operation Allies Welcome, and the CHNV program for Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans, which was created under the Biden administration.

On the second day of President Trump’s second term, the administration announced its intent to terminate humanitarian parole, explicitly targeting the CHNV program while signaling broader efforts to eliminate parole altogether.

Flores-Perilla described the move as part of a campaign to “delegalize” immigrants who already have lawful status, making them vulnerable to detention and deportation.

The Justice Action Center is challenging those actions in Svetlana Doe v. Noem, a lawsuit representing parole recipients who entered the country legally, followed all federal requirements, and were later informed that their parole status would be revoked.

“These are people who did everything the government asked of them,” Flores-Perilla said. “Now the government is pulling the rug out from under them. That is unprecedented and cruel.”

In a separate case, Cherla v. Noem, the organization is challenging the administration’s use of expedited removal against parole recipients, including humanitarian parole holders and asylum seekers who entered through the CBP One program.

Expedited removal allows the government to deport individuals quickly, without a full immigration court hearing or a meaningful opportunity to contest their case. Flores-Perilla said the administration began subjecting parole recipients to this fast-track process, despite the fact that the law does not permit it.

In some cases, she said, individuals appeared at immigration court hearings only to have their cases dismissed, then were detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement and placed into expedited removal proceedings.

“This process has no due process built into it,” Flores-Perilla said. “People are deported before they can defend themselves.”

A federal court temporarily blocked the administration from applying expedited removal to parole recipients, a ruling that Flores-Perilla said has led to a measurable decline in such deportations.

While the government continues to pursue other enforcement tactics, Flores-Perilla said the case shows the courts can still serve as a check.

“These early wins matter,” she said. “They protect communities while we continue fighting for permanent relief.”

Venezuelan Families Face Fear as Legal Protections and Citizenship Rules Are Challenged

As the U.S. Supreme Court agrees to hear a case challenging birthright citizenship, Venezuelan immigrant advocates say fear and uncertainty are intensifying in communities already living with fragile legal protections.

“What we hear every day is terror, exhaustion, and betrayal,” said Adelys Ferro, an activist with the Venezuelan American Caucus. “Families did everything this country asked of them—and now they’re being told their lives could be erased overnight.”

Hundreds of thousands of Venezuelans have registered for Temporary Protected Status (TPS), applied for work permits, attended court hearings, paid taxes, and built businesses. Their children attend U.S. schools, churches, and universities. Yet roughly 600,000 Venezuelans could lose legal protections if TPS is rolled back.

TPS, Ferro said, has become “permanent temporary status,” where every court ruling or policy announcement can instantly change a family’s future. In community meetings and online groups, the same questions dominate: What happens to my children if I lose my work permit? Is it safe to drive? Should we move—or disappear? What happens to my U.S.-born children if I’m detained?

Many Venezuelans fled political persecution, hunger, and violence, Ferro said, only to be treated as threats instead of people seeking safety.

Legally, the main TPS lawsuit affecting Venezuelans is now before the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals and is expected to reach the Supreme Court regardless of the outcome. A final decision could come after October 2026, the deadline for the TPS extension granted under the Biden administration.

Meanwhile, attorneys are pursuing additional legal strategies in federal court to protect TPS holders and preserve work authorization.

Ferro also pointed to a lesser-known crisis: Venezuela has no functioning consulate in the United States. Many Venezuelans lack passports or valid identification, making even voluntary departure difficult or impossible.

Despite the fear and fatigue, Ferro said the community remains determined. “People are scared,” she said, “but they are not giving up. We will stay with them every step of the way.”

“I think about whether I should move to another country,” she said. “But my friends, my family, my entire life are here. I want to contribute to this country.” said a dreamer.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

E Paper

Video

Ritu Marwah

Ritu Marwah

Comments

Start the conversation

Become a member of New India Abroad to start commenting.

Sign Up Now

Already have an account? Login