Sardar Teja Singh Samundri: A Quiet Force Behind Sikh Democratic Awakening

Born in 1882 in Rai Ka Burj village in present-day Tarn Taran district, Samundri rose from modest rural roots to become one of the foremost figures of the Sikh Gurdwara Reform Movement from 1920 to 1926.

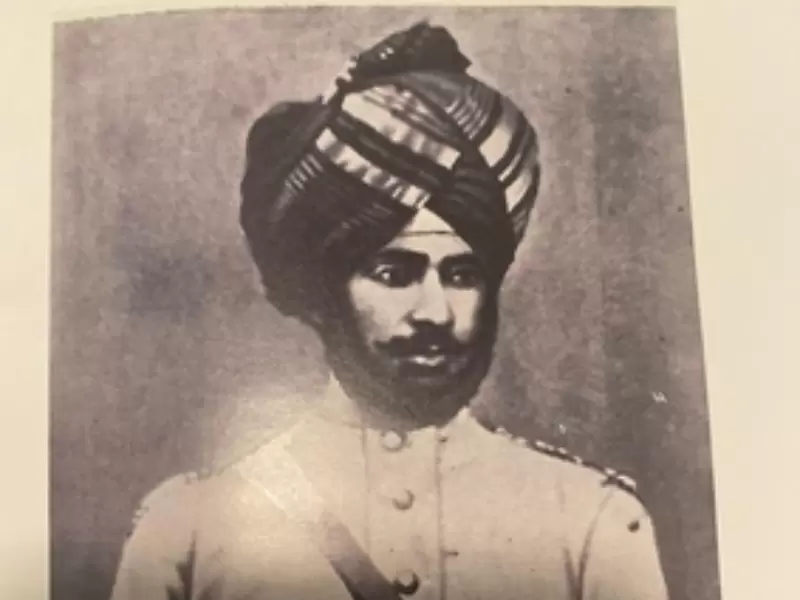

Sardar Teja Singh Samundri / Wikipedia

Sardar Teja Singh Samundri / Wikipedia

Sardar Teja Singh Samundri holds a distinctive and deeply respected place in both Sikh and Indian history for his leadership during the Gurdwara Reform Movement and for helping align Sikh mass politics with the wider Indian freedom struggle.

At a time when resentment was growing toward sections of the Sikh elite, particularly those seen as aligned with colonial authority, Samundri emerged as a moral guide and organisational strategist who channelled public anger into disciplined, principled and collective action.

The presence of Teja Singh Samundri Hall within the sacred precincts of Harmandir Sahib stands as a lasting tribute to his humility, ethical clarity, organisational brilliance and lifelong spirit of sacrifice.

Born in 1882 in Rai Ka Burj village in present-day Tarn Taran district, Samundri rose from modest rural roots to become one of the foremost figures of the Sikh Gurdwara Reform Movement from 1920 to 1926.

His leadership style relied not on rhetoric or spectacle but on the rare capacity to translate moral conviction into structured public mobilisation. He offered both strategic guidance and ethical direction to historic morchas such as Rakab Ganj, Guru ka Bagh, the Keys agitation, Jaito and Nabha.

Among these, the Guru ka Bagh Morcha marked a turning point in India’s struggle for freedom. Sikh volunteers courted arrest and endured brutal repression without retaliation, astonishing colonial officials and inspiring the broader Indian public. National leaders including Mahatma Gandhi, Madan Mohan Malaviya, Swami Shraddhanand and C. F. Andrews openly praised the moral strength of this non-violent resistance.

Despite his influence, Samundri repeatedly declined formal positions of authority because he believed movements weaken when individuals overshadow institutions.

Yet his advice and vision proved instrumental in shaping the formation of the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee and the Akali Dal, thereby laying foundations for democratic functioning within Sikh religious and political bodies.

What distinguished him most was the harmony between his private conduct and public leadership. Master Tara Singh described him as “a complete Gursikh,” emphasising that for Samundri credibility began with self-discipline and leadership with personal example.

His commitment to equality was practical rather than rhetorical. In villages around Amritsar and Tarn Taran, he challenged caste barriers by inviting Dalits to draw water from shared wells and serve him publicly, acts that quietly confronted entrenched social hierarchies in early twentieth-century Punjab. As early as 1917, he also promoted youth and women’s empowerment through the establishment of educational institutions in Sarhali and Lyallpur.

His integrity was matched by material sacrifice. When the SGPC faced a financial crisis and required ₹1.5 lakh to pursue a legal appeal before the Privy Council, only half the amount could be collected.

Samundri mortgaged two murabas, roughly fifty acres, of his own land to provide the remaining ₹75,000. After his passing, when the case was eventually won, his family declined reimbursement. In any era, such an act stands as a powerful contrast to public life driven by private gain.

The colonial administration recognised the moral authority he commanded. In 1923 he and his colleagues were arrested and imprisoned in Lahore Fort and Central Jail, later associated with Bhagat Singh, in an attempt to implicate them in a conspiracy case. In 1926, when pressure was exerted on prisoners to accept conditional release, Samundri led eleven detainees, including Master Tara Singh, in refusing freedom under coercive terms.

Prison thus became another arena of principled resistance. He died in British custody in July 1926 under mysterious circumstances at just forty-three years of age. Public outrage compelled the unconditional release of the remaining prisoners.

Seeking to divide Sikh ranks, colonial authorities quickly announced SGPC elections. Instead, a sweeping wave of public sympathy spread across Punjab and Samundri’s associates secured an overwhelming mandate. This demonstrated that moral authority often endures longer than political force.

Writing later in Akali te Pardeshi, Master Tara Singh observed that Samundri did not become a martyr only in death. His entire life embodied martyrdom. He portrayed a man defined by sewa, devotion, wisdom, love and fearlessness, one without malice, who gave to others before keeping anything for himself. For Samundri, sacrifice was not an isolated act but a permanent condition of life.

By 1923 his stature had grown so widely recognised that he was chosen as one of the Panj Piaras to initiate the kar seva of the Golden Temple sarovar, the first such service since 1842. After his martyrdom, the naming of Teja Singh Samundri Hall within the Darbar Sahib complex became a collective acknowledgment that certain lives shape history without seeking recognition.

Viewed from today’s vantage point, his legacy offers enduring lessons. Credibility arises from personal discipline. Equality must be lived rather than proclaimed. Protest without moral restraint ultimately weakens itself. Institutions must stand above individuals.

Sacrifice need not be dramatic to be transformative. In an age often marked by performative politics and impatient leadership, Sardar Teja Singh Samundri reminds us that quiet courage, steady integrity and institutional vision can leave a deeper mark than the loudest rhetoric.

His was not a life of spectacle but of conscience. That is why it continues to speak across generations.

Discover more at New India Abroad.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

E Paper

Video

Taranjit Singh Sandhu

Taranjit Singh Sandhu

Comments

Start the conversation

Become a member of New India Abroad to start commenting.

Sign Up Now

Already have an account? Login