Inside a real case inspired novel exposing the dark side of enhancement culture

We spoke to author Guruprasad Kaginele and translator Narayan Shankaran about the book ‘Kaayaa,’ which explores the themes of love, lust, gender, beauty, the body, and the soul. Here’s what they had to say.

Author of the book, 'Kaayaa’, Guruprasad Kaginele; Translator Narayan Shankaran / Courtesy: Guruprasad Kaginele, Narayan Shankaran

Author of the book, 'Kaayaa’, Guruprasad Kaginele; Translator Narayan Shankaran / Courtesy: Guruprasad Kaginele, Narayan Shankaran

In an era where the quest for physical perfection intersects with the complexities of diaspora identity, few novels cut through the noise with as much clinical precision and emotional depth as 'Kaayaa.' Originally a landmark work in contemporary Kannada literature, this gripping narrative has now been brought to a global audience in a masterful English translation.

Set against the high-stakes backdrop of Manhattan’s aesthetic medicine scene, 'Kaayaa' (meaning 'Body') follows Dr. Bheem Malik, a celebrity plastic surgeon who believes he has sculpted his way into a perfect American life, only to find his carefully constructed world, and his sense of self, fracturing under the weight of an ethical reckoning.

New India Abroad caught up with the visionary behind the story, Guruprasad Kaginele, a practicing emergency physician and award-winning author, alongside the man who translated this intricate world into English, Narayan Shankaran. Together, they discuss the “enhancement culture” gripping both India and the West, the psychological cost of reinvention, and why some parts of our identity remain stubbornly immune to the surgeon’s knife.

Why did you choose the South Asian diaspora experience in the U.S. to explore cosmetic reinvention, and how does this affect the protagonist's sense of belonging?

Guruprasad Kaginele: This novel is not about belonging or cultural assimilation. The protagonist and his wife believe they have already assimilated into life in the United States. He is a highly skilled plastic surgeon practicing in Manhattan. Though he comes from a small town in northern Karnataka, he is convinced that he has severed his roots. His Indianness is not something he consciously negotiates at the beginning of the novel.

It reappears much later in the story, not as nostalgia or loss, but as a form of reinvention. That shift cannot be explained without reading the novel itself. What unfolds is not a search for belonging, but a confrontation with the illusion of having escaped one’s origin.

How does the novel's origin as a major Kannada work inform its approach to global themes like aesthetic medicine?

Guruprasad Kaginele: The novel was conceived and written in Kannada. It reflects the perception of someone who experiences the world in Kannada and renders that experience into fiction. I am not sure aesthetic medicine is truly a global theme. India, in many ways, is still a generation behind the West in its everyday applications.

This is not to say that India lacks beauty-enhancement practices, but ideas such as drive-through Botox or lunch-hour fillers are not part of common cultural vocabulary. Aesthetic medicine is still distant from the average household, especially for people who read this work in Kannada.

I was uncertain how such a theme would be received by Kannada readers, but it was received surprisingly well. Readers familiar with my work expect these kinds of explorations, and that familiarity helped anchor what might otherwise seem unfamiliar.

How does the pursuit of enhancement in India compare to the motivations you explore in the novel’s U.S. setting?

Guruprasad Kaginele: In India, particularly among the middle class, beauty was traditionally seen as unnecessary for everyone. It was reserved for film stars and models. Consumer culture has altered this sharply.

As consumerism expands, more professions now demand visual appeal—flight attendants, receptionists, retail workers, and salon employees. The culture insists that everything be attractive, including regular people. Once individuals enter this system, the pressure to conform becomes intense.

In this sense, beautification is not merely a personal choice but an extension of consumer culture. The motivations explored in the novel’s U.S. setting represent this pressure taken to its logical extreme, where enhancement becomes routine, normalized, and unquestioned.

How did your medical experience inspire and challenge you when adapting a real case into this ethical and psychological narrative?

Guruprasad Kaginele: I’m an emergency physician, not a plastic surgeon. I don’t create beauty—I usually see its consequences. In the ER, cosmetic work appears through complications and human stories beneath altered surfaces. The imagery of one patient went on to stay with me. She was an aspiring actress who had undergone extensive cosmetic procedures and was also terminally ill with cancer.

As the disease wasted her body, everything natural collapsed—except the surgically altered parts. Her lips, breasts, hips, and abdomen remained unchanged, standing out against her frailty. It struck me deeply: man-made beauty can outlast the body itself. The image was unsettling and unforgettable, and it stayed with me long enough to become the seed for this novel.

Does Kaayaa portray aesthetic medicine as an expression of patient autonomy or a tool of medical power/control?

Guruprasad Kaginele: Kaayaa is really about patient choice. The novel sees aesthetic medicine as something people choose for themselves, not something forced on them by doctors or systems. The surgeon doesn’t push change onto anyone—he simply responds to what patients come asking for.

For the patients, these procedures aren’t about being controlled or manipulated. They are conscious decisions about how they want to live in their bodies. The body becomes a place where choice is exercised, not taken away. If there’s any tension in the novel, it’s not about medical power. It’s about what it means to choose—how sure we are of our choices, and what changing ourselves actually costs us. The book respects that agency, even as it quietly asks what lies beneath the decision to alter one’s body.

Having said that, some medical procedures and drugs change the body so drastically that patients are almost pushed into aesthetic correction. The surgery isn’t forced, but it isn’t entirely voluntary either—it’s not what they would have chosen otherwise. That is the irony of weight-loss surgeries and drugs.

What does the novel ultimately suggest about the human impulse to fight aging and the erosion of time?

Guruprasad Kaginele: The novel does not set out to suggest anything. It observes. When the obsession with beauty intensifies, and when surgeons begin to believe they can create it at will, the human body risks becoming just material—flesh to be shaped. That may sound extreme, but the novel uses creative exaggeration to explore how a surgeon’s imagination and authority can begin to influence his work.

At that point, aesthetic surgery turns into an industry responding to endless demand. I’m not offering a moral or a conclusion. I’m simply holding up a situation and letting the reader decide what it reveals about our urge to resist aging and time.

In the #MeToo-like reckoning, what did you hope to explore about accountability when private ethical choices are met with public judgment?

Guruprasad Kaginele: I wasn’t trying to comment on the #MeToo movement itself. What interested me was what happens when private ethical choices—especially in medicine—are suddenly exposed to public judgment.

In cosmetic medicine, the line between clinical palpation and sensuous touch can be very thin. How do you tell the difference? What if a surgeon is licentious? Where does informed consent actually begin and end? What if a patient consents to a procedure but not to every kind of touch that comes with it?

These are uncomfortable questions, but they are real. The novel explores accountability in this grey area—not to deliver verdicts, but to show what happens when these blurred boundaries are no longer allowed to stay private.

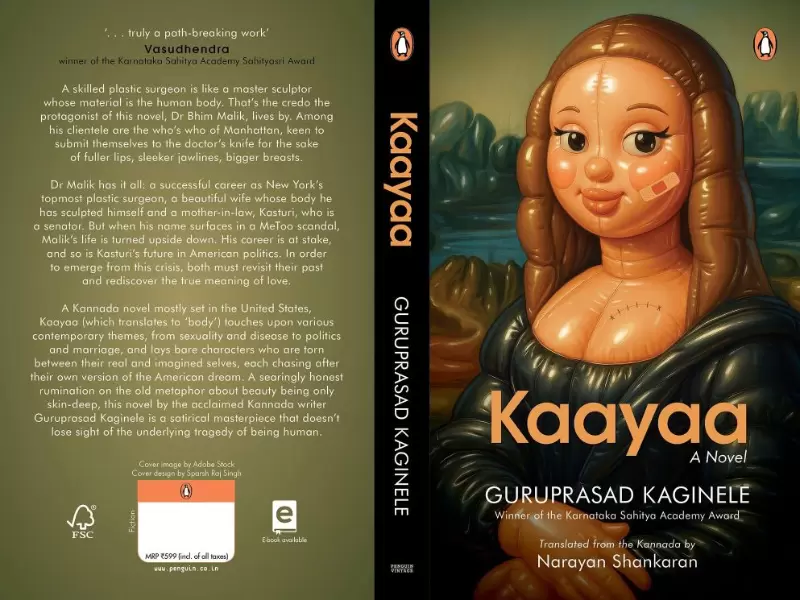

Book cover of 'Kaayaa' / Courtesy: Guruprasad Kaginele

Book cover of 'Kaayaa' / Courtesy: Guruprasad KagineleHow essential was it to deconstruct the personal myths (of success, marriage, and self-image) that the protagonist built?

Guruprasad Kaginele: This is where Kaayaa is deeply rooted in its origin as a Kannada novel. Malik and Pari come from small towns in northern Karnataka but have consciously embraced an American, especially Manhattan, lifestyle. They haven’t just adapted externally—they’ve tried to reshape their core values as Indians, including beliefs around marriage, monogamy, and mutual exclusivity.

Malik’s profession as a successful celebrity plastic surgeon shapes his worldview, and his choices inevitably affect Pari. The novel also explores other relationships—like Samantha and Honey, who start as Malik’s patients and enter a more complex dynamic, and Kasturi, Samantha’s mother, who becomes entangled in what seems a redundant case.

Success, self-image, and relationships are constantly questioned against each character’s independent upbringing and values. Malik—originally BheemasenaRao Raghothama Rao Malakheda—believes he has comfortably transformed into Malik, but he undergoes a profound personal reckoning, realizing that identity, success, and desire cannot be fully controlled or reinvented.

Since KAAYAA is a deep psychological portrait, what were the main concerns in ensuring the nuanced cultural and emotional language of the Kannada original was preserved in the English translation?

Narayan Shankaran: While translating any vernacular literary fiction into English, preserving the nuanced cultural and emotional language of the original is a major concern. However, the translation of Kaayaa demanded a slightly different approach. As Guru noted earlier, the protagonist and key characters in the novel believe they have severed all ties with their roots, so their cultural and emotional language has also shifted dramatically. With the story set in the US, the need to retain a strong Kannada linguistic flavor was minimal. That’s why, to a large extent, the translated Kaayaa reads like an original English novel. Yet, when these characters face situations that shatter their delusions of escape from their origin, their inherent cultural and emotional parlance merges seamlessly.

What challenges were overcome to translate the book as authentically as possible?

Narayan Shankaran: When I took on translating Kaayaa, I was well aware of the challenges ahead. For one, I was worried that my refined, conservative style might not nail the novel's raw energy and vibe.

Set in a modern American world, it called for a more gritty, in-your-face language that was way outside my usual comfort zone. I also needed to incorporate precise medical parlance to authentically depict the treatments and procedures in the world of plastic surgery.

Additionally, having translated Guru’s short stories before, I knew that honoring his unique narrative style required not just conveying what he says but also capturing the subtle nuances of what he eloquently leaves unsaid. But with Guru’s steadfast support, I felt quite up for it.

His insights helped us strike a contemporary—and sometimes even crude info without sacrificing the narrative’s soul. Having given my best to stay true to Guru’s vision, I now hope readers will find that same resonance in the work

What would you like our readers to know about the book?

Guruprasad Kaginele: A translated Kannada work, this contemporary literary novel stands apart from other works in the same genre. Narrating Indian characters fully absorbed into American life, it explores the quiet but persistent pull of ‘substratum’ shaping cultural identity. The book pushes further into elemental themes of love, lust, gender, beauty, the body, and the soul, offering a modern, urbane story with lasting emotional depth.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

E Paper

Video

Pallavi Mehra

Pallavi Mehra

.png)

Comments

Start the conversation

Become a member of New India Abroad to start commenting.

Sign Up Now

Already have an account? Login