Will the U.S. Courts Strike Down the Tariffs on India?

If the Supreme Court rules against the administration in this case, the President could still pursue tariffs under other statutory authorities.

Indian flag and the word / REUTERS/Dado Ruvic/Illustration/ File Photo

Indian flag and the word / REUTERS/Dado Ruvic/Illustration/ File Photo

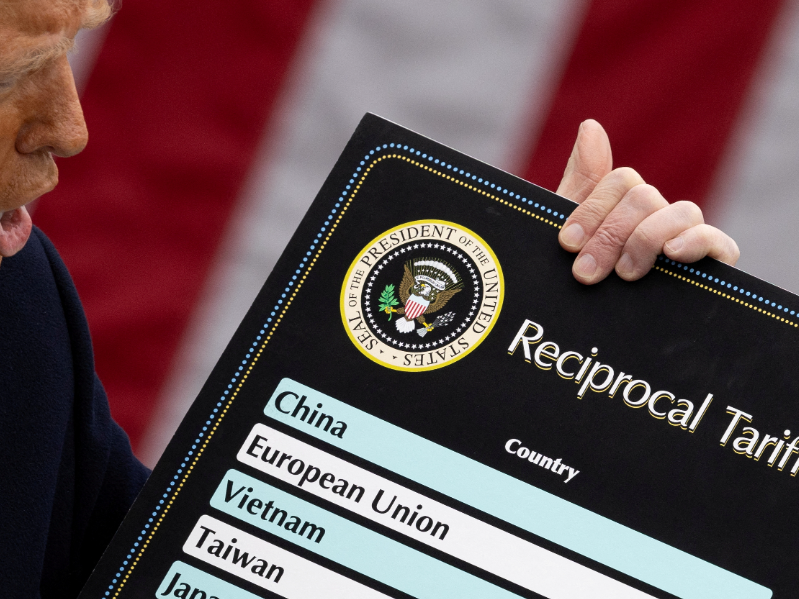

Just two days after President Trump’s punishing 50% tariffs on Indian imports went into effect, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit ruled that he had no authority to impose them.

The Trump administration argued that Congress had delegated authority to impose tariffs under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) of 1977. However, the appeals court ruled that IEEPA does not give the President that power. What does this new court case mean for tariffs on India and other countries?

The 50% tariffs on India will remain in effect until a decision by the U.S. Supreme Court is issued. The administration has asked the U.S. Supreme Court for an expedited review and the Court has agreed to hear oral arguments for the case in early November.

A final decision by the Court could come as late as June 2026 even though the administration will ask for an earlier ruling to resolve the uncertainly.

Also Read: Tariffs and Trust: Preserving a Vital Strategic Bond

Courts are generally cautious about reading broad powers into statutes unless Congress has clearly granted them. The IEEPA makes no explicit mention of “tariffs” or “duties.” During a declared national emergency, IEEPA does allow the President to “investigate, regulate, or prohibit… imports” from foreign nations. Trump argued that the word “regulate” imports encompasses raising tariffs since tariffs are a common tool in international trade. The appeals court, however, found that IEEPA does not give Trump the power to issue the widescale tariffs he has issued over the course of his presidency.

In the past, the Supreme Court has allowed Trump to advance key parts of his agenda—particularly on immigration—through emergency orders issued without full briefing or oral argument. If the Supreme Court rules against the administration in this case, the President could still pursue tariffs under other statutory authorities.

First, Trump could rely on Section 122 of the Trade Act of 1974, which allows him to impose up to a 15 percent tariff for 150 days in response to a balance-of-payments emergency. After that, however, Congress would need to approve the measure. This would be far less sweeping than the 50 percent tariffs currently imposed on India.

Second, though it has not yet been used before, Section 338 of the Tariff Act of 1930 authorizes tariffs up to 50% against countries that discriminate against or impose unreasonable charges against U.S. Trump could surely frame his tariffs in this way.

Third, Trump could invoke Section 232 of the Trade Act of 1974, which permits tariffs on national security grounds. Sectoral tariffs on autos, steel, aluminum, and copper have already been imposed under this authority, and there is a pending investigation into (among other things) pharmaceuticals under Section 232.

Pharmaceuticals are currently exempt from Trump’s liberation day tariffs, but he may eventually impose them under Section 232 after the U.S. Commerce Department issues its final report to the President on the investigation. India supplies nearly half of all generic drugs sold in the United States.

Finally, Trump could also try to get explicit authorization from Congress for the tariffs. Although Republicans currently control both chambers, many traditional conservatives remain pro–free trade. Lawmakers may also hesitate to vote for tariffs because they could actually harm businesses and consumers in their states.

Regardless of the U.S. Supreme Court’s ultimate decision, the tariffs will remain in place for at least several more months and President Trump may find other ways to reimpose some of them even if he loses at the Supreme Court. U.S.–India relations are unlikely to improve in the near term.

Trump appears to be using tariffs to force India to align with the United States by disentangling itself from countries that the United States disfavors. The irony is that the tariffs appear to be having the contrary effect—India is moving closer to China and Russia.

The author is Professor of Law at Seattle University School of Law and Founding Director of the Roundglass India Center.

(The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of India Abroad)

1758210324.png) Sital Kalantry

Sital Kalantry

.jpg)

Comments

Start the conversation

Become a member of New India Abroad to start commenting.

Sign Up Now

Already have an account? Login