Pakistan’s mounting military casualties and the unequal burden of war

For decades, Pakistan’s military has portrayed itself as the sole glue holding a fractious nation together. But that has changed in the recent decades where military has transformed into a catalyst of insecurity.

FILE PHOTO: A police officer walks past damage at the site, after militant attacks, in Quetta, Pakistan, February 1, 2026. / REUTERS/Stringer/File Photo

FILE PHOTO: A police officer walks past damage at the site, after militant attacks, in Quetta, Pakistan, February 1, 2026. / REUTERS/Stringer/File Photo

It is barely a month into 2026 and Pakistan, it appears, is already sliding toward a grim year ahead. In just the first month, there have been nearly a hundred security forces casualties, including a lieutenant colonel targeted while traveling in a private vehicle on January 28, besides dozens of civilians.

If this trend holds which look highly likely given increasing strength of ethnonationalist insurgency in Balochistan and Islamist militancy in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, it could turn into the deadliest years for Pakistan Army led security forces in the country.

On Jan.31, Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA) launched coordinated assaults across as many as fourteen cities in Balochistan. Labelled as Operation Herof 2.0, hundreds of BLA fighters struck military and provincial government installations from provincial capital Quetta to port city Gwadar, from Turbat to Panjgur, demonstrating a level of planning and reach that Pakistan’s security planners have long insisted was impossible.

While the BLA claimed 84 security officials killed and 18 taken hostage, Pakistan Army’s DG-ISPR acknowledged the death of 17 soldiers and 31 civilians while claiming to have killed 177 BLA fighters. It has been over four days and it appear BLA seems to have entrenched its control over many areas across the cities, particularly Noshki, with Pakistan Army struggling to remove the fighters despite using indiscriminate force, including aerial attacks.

The contestation over the casualties on either side aside, this latest attack demonstrates how the insurgency in Balochistan has evolved from a peripheral “irritant” into a strategic challenge capable of overrunning state facilities and humiliating Asim Munir led Pakistan Army in real time. But this was not an isolated outburst as independent monitors have recorded as many as 87 separate insurgency incidents in January alone.

According to the Pakistan Institute of Conflict and Security Studies (PICSS), since General Asim Munir assumed command in November 2022, the army and its affiliated forces have lost 2,017 personnel, with a record 857 deaths in 2025, besides over 1100 civilian fatalities during the same period. These figures rival the darkest years of Pakistan’s counterinsurgency campaigns, yet they receive only fleeting acknowledgement in national discourse.

But what distinguishes the military casualties is not merely their number but more importantly who is dying. According to the media reports about insurgent incidents in Balochistan and militant incidents in KP, the bulk of losses are borne by the Frontier Corps (FC) and the Levies, which are paramilitary formations recruited largely from Baloch, Pashtun, Sindhi and other non-Punjabi communities. It is these units that patrol the most dangerous terrain, man remote checkpoints and therefore become the first line of responders when insurgents and militants strike.

On the other hand, the Punjabi soldiers, which dominate the officer corps and the central command structure, are far more insulated from direct combat.

Such a division of risk is not accidental but reflects the very psychology of the Pakistani state. The military remains overwhelmingly Punjabi as demonstrated by its ethnic demographics which has 70 to 75 percent Punjabis, 14–20 percent Pashtun, 5–6 per cent Sindhi, and merely 3–4 Baloch. The officer class is even more skewed in favour of Punjab with Punjabi officers commanding Frontier Corps and Levies.

While Baloch soldiers are ordered to fight Baloch insurgents and Pashtun recruits are sent to battle Pashtun militants, the arrangement guarantees local resentment. Under General Munir, this Punjabi dominated military establishment has acquired a political purpose of consolidating every lever of power of the state. Since his elevation in 2022, Pakistan has gradually transformed into military led hybrid rule through a carefully calibrated yet brazen constitutional gerrymandering which has rendered elected institutions largely irrelevant with real authority in the General Headquarters in Rawalpindi.

As such, the Punjabi dominance within the army becomes the pillar of regime stability, while non-Punjabi paramilitaries serve as expendable shock absorbers for an unpopular security project.

For decades, Pakistan’s military has portrayed itself as the sole glue holding a fractious nation together. But that has changed in the recent decades where military has transformed into a catalyst of insecurity by designing Islamabad’s imperial approach towards non-Punjabi provinces which sustains on coercion than consent. Nowhere is this more evident than in Balochistan. For decades the province has been treated through a colonial lens of resource extraction of gas and other mineral copper with little investment in its people.

While political dissent is answered with enforced disappearances and economic demands are framed as treason, such policies have further alienated people and contributing to the cause of ethnonationalist groups. The BLA’s latest offensive not only demonstrated scale and intensity but also its social breadth with men and women fighting side by side, reportedly including a grandmother and a newly-wed couple. But for Pakistan, it is the state’s policies which have ensured that the cause of Baloch nationalist groups was no longer a fringe phenomenon but entrenched within the society.

Likewise, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa tells a parallel story. Here, Pakistan’s proxy policy of terrorism as instruments of regional policy, particularly against Afghanistan and India, has unravelled as many of those groups, including many factions within Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) have now turned inward. And despite repeated anti-militancy campaigns by the army, militant networks have reconstituted themselves with each case of military violence and emerging stronger.

General Munir’s response has been to double down by expanding military courts, criminalising online dissent, and relying ever more on auxiliaries like the Frontier Corps and Levies. This strategy is less about defeating insurgency than managing it at tolerable cost which is however paid overwhelmingly by non-Punjabi bodies. On the other hand, Punjabi soldiers remain guardians of regime stability in Islamabad and Lahore. The contrast is visible: armoured calm in the centre, burning peripheries at the edges.

History suggests that armies can survive defeats but what they cannot survive is a perception of injustice within their own ranks. Asim Munir led Punjabi military establishment of Pakistan Army continues outsourcing its dirtiest wars to non-Punjabi formations while reserving privilege for the Punjabi core. It is a recipe of sowing fractures that may one day reach Rawalpindi itself.

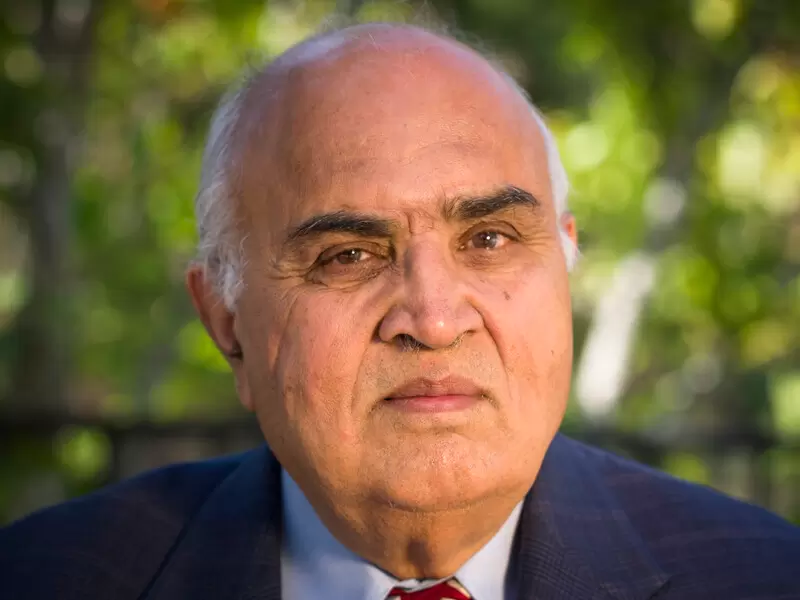

The writer is an author and a columnist. He has authored more than 15 books including 'Taliban: War and Religion in Afghanistan'.

(The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of New India Abroad)

Discover more at New India Abroad.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

E Paper

Video

1744362597.jpeg) Arun Anand

Arun Anand

Comments

Start the conversation

Become a member of New India Abroad to start commenting.

Sign Up Now

Already have an account? Login