Are there Ethics in War: A Vedic Perspective

How advanced were the indigenous peoples of India, when it comes to their code of ethics, rules of conduct, standards of etiquette during periods of conflict?

Representative Image. / Pexels

Representative Image. / Pexels

According to the largely accepted history of India, which was mostly written by Western Indologists in the last couple of hundred years and still being taught in schools even inside India, the aborigines of India they called Dravidians were uncivilized people, who were pushed down south by invading hordes from Central Asia around 1,500 BCE they labeled Aryans. These natives were supposedly primitive with no culture, science, philosophy and fought with stone-tipped arrows. These Indologists also explained away India’s rich ancient literature called the Vedas, and the associated oldest language - Sanskrit - as having been brought by these ‘invading hordes’ of Aryans from outside.

The problem with this scenario is that the vast corpus of literature called the Vedas has no such memory of Central Asia and describes places, events, and surroundings native to India. Advanced philosophy and well-developed code of ethics and laws - Nyaya- practiced in India during ancient times, are described in many places in the Vedas.

One of the questions that then arises is - How advanced were the indigenous peoples of India, when it comes to their code of ethics, rules of conduct, standards of etiquette during periods of conflict - prior to, during and post wars? Did they fight wars before the supposed ‘invasion’ or ‘migration’ of ‘Aryans’ ?

When we think of war, mindless killing and human rights violations come to mind. Does an ethical war ever exist? Is war more than brute force and incomprehensible violence? How advanced were the Indigenous people of India, when it came to their code of ethics, rules of conduct, and standards of etiquette especially during periods of conflict - prior to, during and post-wars?

There has been some discussion about Ancient Indian cultures having a strict code of conduct that was well known and strictly adhered to by all parties during a war. What were these codes and etiquettes of ethics and valor and moral standards?

This paper will dive into Vedic Literature to bring out and study these codes, their antiquity, their extent, and the consequences of violating these codes. We will also look at other aspects of rules and governance that will help shed light on these codes of conduct.

Documents like Niti Shastra which list ethical principles for many instances will be studied to understand these codes of ethics. Some other historical documents that discuss these codes of ethics include the Vedas, Epics, Puranas, Dharma Shastras, and testimonials of foreign visitors.

If time and space permits, comparison will be attempted to see how these codes compare to relevant and contemporary codes from cultures outside of India.

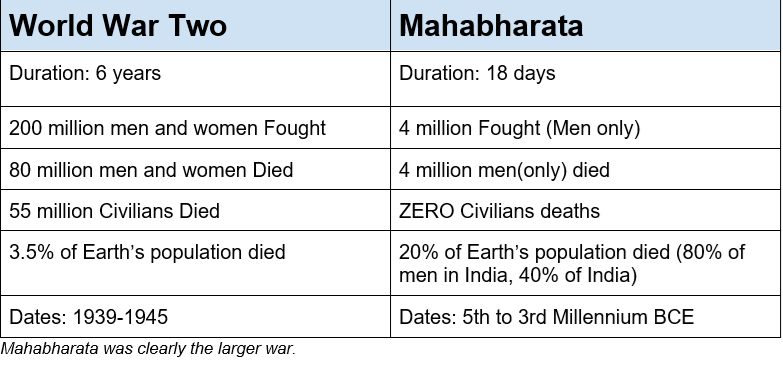

MAHABHARATA - LARGEST WAR THAT MANKIND EVER FOUGHT:

After some preliminary research, we realized that getting data on war related behavior for our paper would be easy. After all, one of the main focuses of our study was ancient India, which happened to have experienced the largest war the world has ever witnessed - by far.

A Side by side comparison of the assumed largest war ever, vs the real largest war ever follows.

WAR SEEN FROM AN ANCIENT VEDIC INDIAN LENS:

In Ancient India, religion dictated all facets of life during Vedic times. There were checks and balances to the King’s powers via a council of ministers and Rishis and Raj Gurus. There were also open discussions of Niti -policy and conduct - in an open ‘Sabha’ or Court - similar to today’s town hall meets. The decision to Start a war had to go through a rigorous process of having to meet moral and ethical standards. There were guidelines not only for initiating and participating in a war, but also the conduct of the warriors during and after wars.

The options of Sama, Dana and Bheda methods of negotiation had to be exhausted before a Kingdom could decide to go into war and aim to do Danda or punishment to force proper behavior. These four options were collectively called the Chatur Upayas.

TWO TYPES OF WARS:

Ancient Indian Kings took pride in fighting righteous wars, which literally translated to, and were known as - Dharmayuddha. These types of wars had to follow certain moral and ethical rules established by the seers and Rishis and other learned men. A Dharmayuddha dictated that wars be fought mostly in defense against unrighteous aggressors. Diplomacy was used via use of Doot’s ( envoy or Ambassador), and extensive negotiations were suggested and often practiced for the sake of avoiding loss of life and resources in a war.

DharmaYuddha (Righteous or Dharmic war) - followed standards understood and regulated by the warrior community and the Rishis, was fair and just, and there was strict enforcement by the rulers and the society. Just like Dharmic principles, the situation decided the correct code of conduct. For example, even though most Vedic literature harps on non-violence, violence committed in certain circumstances - for eg. - to prevent larger violence, was considered the righteous or dharmic path to follow. Of course one can find exceptions, but as per Vedic literature, extended periods in ancient Indian history witnessed the practice of DharmaYuddha principles.

Social structures and state administration of a defeated nation were left intact, and property was not destroyed. Often the subjugated King was re-installed to rule the land, and the main change brought about was the acknowledgment of the suzerainty of the winning king over the defeated king's land.

We will list some of the specific ethical principles followed during DharmaYuddha later.

The other kind of war, was known as Kuta Yuddha (UnRighteous or adharmic war) - was done covertly, use of spells was allowed, and the principles followed were the exact opposite of ethical ones, where amoral and deception was used.

There were three kinds of victory from a war. Dharmic victory (Dharmavijaya) which followed the principles of Dharma Yuddha.

Whereas Victories gained by using Kuta Yuddha were of two kinds.

Lobha Vijaya where the victorious king appropriated resources and territory of the loser, but left the administration intact, and did not touch civilians, children or women.

Asura Vijaya was the kind of victory where evil knew no bounds, and the loser king was deposed, all his kingdom annexed, women and children were harmed, institutions and infrastructure was burned down.

It should be noted that these three types of victory loosely map onto the Three Gunas , also known as TriGunas; namely - Sattvic (Dharma Vijaya), Rajsic (Lobha Vijaya) and Tamsic (Asura Vijaya).

WHAT DOES VEDIC LITERATURE SAY ABOUT DHARMAYUDDHA:

WHEN IS WAR JUSTIFIED

As opposed to the other ancient civilizations at the time, the people of ancient India believed that war was a last resort. War wasn’t to be waged just to conquer more land or dominate people. It was a method to ensure that good prevails over evil and Dharma was maintained. In the Manusmriti, the following `Caturopāyas’ (the four means) are defined as the different ways to deal with conflict: Sāma (conciliation), dāna (gift or bribery), bheda (subversion of allies), and daṇḍa (punishment) (Manu 7.109).

In an attempt to avoid war, the first 3 means are various methods of diplomacy, and if that all fails, is war a justifiable final alternative. Only if the first 3 of the ‘Caturopayas’ are deemed ineffective, which in most cases it had proven not to be, then war was the last resort and considered the right thing to do (dharmic). If there were any means to use the former three Caturopayas, war would not be an option.

WHO AND WHAT CAN BE ATTACKED

In various Vedic scriptures, it is explicitly mentioned who and what can be attacked as well as those who are considered under the protected class. For instance, in the Mahabharata it is said that one ought not to engage an unarmed warrior, and specifically that one should not attack one who is wounded, nor one whose sword is broken, whose bowstring has been cut, or whose horse or chariot have been compromised in some manner.

Armies should only engage armies, and chariot warriors should only engage other chariot warriors (Mahabharat 12.96.1–13). It goes on to further elaborate and set grounds that a warrior could only fight against those of similar strength in terms of equipment and skills. Those fighting on a vehicle, whether it be a horse or chariot, could not engage in a fight against armies on foot. Collective groups fighting against one individual was prohibited.

If for any reason the enemy was at a disadvantage due to loss in armor, physical ability, or even mental agility from grieving over those they lost, they were to be spared and considered ineligible to partake in the battle. When the enemy was wounded, exhausted, or surrendering altogether, the war was to be halted and soldiers who left the battleground were not to be attacked. Along with this, any sort of supplier of ancillary help like the charioteer, were not part of the war, and hence were to be left alone.

Overall there was a mutual consensus among all parties at war that once a soldier is at a clear disadvantage, he could gracefully retire , and his exit should be facilitated.

(Mahabharat 6.1.26–34)

WERE DHARMAYUDDHA PRINCIPLES FOLLOWED DURING ANCIENT (VEDIC) INDIA?

There is a lot of confusion, especially among scholars about how to evaluate situations of war during the Ramayan and especially Mahabharata.

During the Ramayana, which many scholars date to between the 14th and 5th Millennium BCE, strict codes of conduct were followed in justifying wars, during wars, and post-wars.

Negotiations were given a chance, and fair warning was given to Ravana and other Adharmics before war was declared. Even the Adharmics respected the prevailing rules and etiquettes, as is evident by Ravana deciding to treat Ambassador Hanuman per the protocol. During the war, strict guidelines of Dharma Yuddha were followed. After wars, a defeated kingdom was not ravaged, its citizens and survivors treated with respect, and its native royalty was installed as king.

The Mahabharata is commonly dated to between the 6th and the 4th Millennium BCE. It is regarded as the largest war on Earth- ever - bar none. A large portion of the population of men involved in the war, perished in this great war. Per the Mahabharata, 18 Akshouhini men participated, and most of them perished. That comes to about 4 million men, out of an estimated 10 million population of men worldwide, assuming a 6th Millennium BCE era for the war. The number of countries of the inhabited world that participated in the war was also very significant.

A few notable incidents in the Mahabharata are often pointed out as evidence of acts which did NOT follow Dharmic Principles of DharmaYuddha.

1. Killing of Bhishma by Arjun, by using Shikhandi as a shield. Bhisma was the commander of the Kaurava Army, and was a fierce warrior, and was unbeatable. He had personally caused huge losses to the Pandava army in the first 10 days of war as the commander, and was seen as a reason the other side would face defeat.

2. Drona then took over command of the Kaurava army, and the Kauravas corner Pandava Arjun’s son Abhimnyu and after snatching his weapons and chariot,making him defenseless, gang up on him in a group of six warriors, and then kill him. (MB 7.47-8)

3. Killing of Bhurisrav (Kaurava side) by Satyaki (Pandava). Originally Arjuna unfairly severed the arm of Bhurisrav with an arrow, WHILE Bhurisrava was engaged in a duel with Satyaki (mb 7.118)

4. The Kaurava Commander Drona is killed unfairly by Arjuna, by misleading Drona about his son Asvattama’s death.

5. On the 16th out of 18th day of the war, Karn whose chariot is stuck in the mud, is killed unfairly by Arjun. MB 8.66

6. On the final day of the battle, Pandav Bhim, kills Kaurav Duryodhan by unfairly hitting him below the belt. MB 9.57

7. Enraged by the above indiscretions by the Pandavas Aswathama the Kaurav son of Drona - sets fire to a Pandava army camp, and unfairly kills many sleeping Pandav soldiers. MB 10.1

While these indiscretions do go against the prevailing dictates of DharmYudh principles, the following should be kept in mind:

1. Onlookers and participants and ‘celestial’ voices disapproved and chided the adharmic acts mentioned above.

2. The side that committed these acts also disapproved and warned their side never to commit the act.

3. That same side also repented and was ashamed of these acts.

4. A partial justification by the committers of these unapproved acts was that the victims had committed strong adharmic acts themselves. Bhisma by not dividing the kingdom fairly, not speaking up after the illegal acts of Kaurav’s trying to kill Pandavas, insulting Draupadi etc. Karna because he insulted Pandavas and Draupadi, and lauded her disrobing, and killing a cow. In the minds of the Pandavas who committed adharmic acts, the unfairness did not start with their own actions during the war, they considered the adharmic acts of the Kauravas when deciding how to handle the task (war) at hand.

The Kaurava side similarly cited the unfair killing of Bhim, Bhurisrava, Karna, Drona by the Pandavas. In other words, once the adoption of unfair practices started, one heinous act justified the other, until the whole army on both sides was almost wiped out.

5. Some of these questionable acts by the Pandavas, if not committed, would cause results that would be of greater loss to mankind.

6. Above acts are some notable exceptions to an otherwise DharmaYuddha, which was much bigger than these incidents. While there is debate on the interpretation of how many died, the war was so big that a vast majority of all males perished in the war. So some unfair acts that started occurring on the 10th day of a 18-day war, may not seem like a gross violation of Dharmic rules, especially given their rare occurrence. Keeping in mind that the war only involved members of the Kshatriya community, the other communities were not touched.

7. There was a large effort on the part of Sri Krishna prior to the war, to reach a peaceful settlement such that the war could be avoided. Sri Krishna noted that the Kauravas were not doing negotiations in good faith, and realized that their transgressions were adharmic. He was an impartial mediator, since both sides were his cousins.

Therefore focusing on these few transgressions in a massive war that largely followed the rules of DharmaYuddha, cannot be considered an impartial or holistic evaluation.

FOLLOWING OF DHARMAYUDDHA PRINCIPLES AFTER THE VEDIC PERIOD:

During Ancient times DharmaYuddha principles were followed very religiously. By the time of the Mauryan dynasty (1st millennium BCE), the reasons to get into war began to be fuelled by imperialist and expansionist attitudes, but the code of ethics in fighting the war (Jus in bello) remained mostly intact.

This is possibly because Kautilya, the Chief Minister of the Maurayan king Chandragupta, saw many small neighboring states constantly at conflict with each other, which he realized was very disadvantageous to his fellow natives of India, and had led to Greeks and other invaders being able to conquer most of north and west of India, and being poised to take over all of India.

Kautilya was shrewd enough to realize that strict following of DharmaYuddha principles would not work in creating a powerful united kingdom that would be able to repel the takeover of India by foreign invaders - at least not in due time. Kautilya wrote extensively about attacking kings who were not good rulers, and about being just and fair to conquered peoples.

He was not afraid to use KutaYuddha when needed, but also followed DharmaYuddha whenever possible, especially if it also aligned with good and righteous policy that helped his own kingdom rule better and keep expanding. He did not advocate pillaging and ransacking defeated lands and its subjects. He asked his soldiers to help captured peoples, give them tax concessions, and induce them to settle down and farm their lands.

To make the new subjects feel comfortable, Kautilya even suggested that the King and his emissaries adopt local costumes and customs, worship local deities, attend local events etc. He instructed to especially never touch the property of the defeated subjects of a won territory, as that is not only unrighteous but also causes ill will towards the kingdom and is not a pragmatic policy for the King.

Many scholars have incorrectly used Kautilya’s rule as an example of how the traditional Dharma principles were thrown out the door. While he did use principles that would be considered unrighteous during Ancient Vedic times, especially when getting into wars (Jus ad Bellum) he does suggest in his Arthashastra, and also practiced, many of the righteous principles as laid down in the Dharmasastras during and after wars (Jus in Bello) .

After the Gupta period, KutaYuddha became common, and unrighteous wars (both the reason for war and the conduct during the war) started to become the norm. The invading forces from outside India were not a creed that followed any rules or code of ethics during wars, and it was immediately realized by Indian Kings that if Dharmic rules were followed, it would lead to devastating losses and loss of independence, culture, religion and identity.

DharmaYuddha practices that have influenced modern day International laws:

Discussion on IHL and DharmaYuddha principles - Similarities and Divergences

.png)

DID OTHER NATIONS HAVE DHARMAYUDDHA LIKE PRINCIPLES?

Western concepts of war refer to two principles that the west suggests that all parties in a war should adhere to. Right reasons to go to war, and Right conduct during war, are referred to by latin phrases Jus ad bellum and Jus in Bello respectively. The solemnity of Latin falsely confers onto these phrases the false appearance of being very antique. In reality, these Latin phrases first popped up ONLY during the League of Nations, the precursor to the UN, founded in 1920 to deal with international issues centered around war, and to bring peace. The principles themselves were rarely used until after the second World War in the late 1940’s.

Philosophically these matters were discussed by St. Augustine in the 4th century CE, and by Thomas Aquinas in the 13th Century CE.

The League of Nation’s covenants dealt with providing disarmament, just treatment of native inhabitants, human and drug trafficking, arms trade, protection of minorities in Europe, among other things. What should be obvious from this partial list is that while these were problems plaguing Europe for a long period, India was not known to have these issues in its long history.

Jus ad bellum principles state that wars must meet the criteria of Just cause, proportionate action such that the casualties do not outnumber the problem itself, right intention, right authority that declares war, reasonable chance of success, and right intent.

A quantitative analysis by Dorn et. al, shows that American wars in Libya 1986, Lebanon(1958), Panama(1989), Grenada(1983), Vietnam(1954) and Iraq 2003, were not considered just wars, while the world wars(1914, and 1939), Gulf war(1991), Korean war(1950), Bosnia(1992) passed the test of just wars. The analysis was based on a survey of over 100 International studies experts.

Even though most of Europe’s wars occurred prior to the coining of these two Latin phrases in 1920, it is well accepted that the wars were based largely on unjust reasons. Many were caused by imperialist goals of fighting with colonies being taken over, or getting in wars with other European colonial powers over colonial territories. Then there were wars based on religion, including within Christendom like the Wars of reformation fought between the Roman Catholic Church and the Lutherans. Other religious wars were based on fighting with the Islamic Caliphate.

CONCLUSION:

Codes of ethics related to just causes of getting into war, and related to prescribed behavior existed in India since very ancient times. Vedic literature is very vast, and covers historical records going back many millennia. The Ramayana which is considered to be from somewhere between 13th and 5th millennium BCE, and Mahabharata which is primarily a story of a great war, is considered to have happened sometime between the 5th and 3rd millennium BCE.

The Mahabharata war is an excellent case study in Indian war ethics, since it was the largest war that humanity ever fought.

Even in such antiquity, ancient Indians had strict codes of dharmic principles encoded in a principle known as DharmaYuddha. The principles had a strict code of conduct of evaluation of all acts by the state using a lens of Dharma or fairness. Examples abound of extended negotiations initiated in order to stave off wars, failing which wars occurred.

A lot of emphasis was placed on just behavior during wars as seen from the research presented. The principles were followed very strictly during ancient times, and in fact have formed the backbone of the modern International Humanitarian Laws (IHL) currently in use.

Transgressions of DharmaYuddha principles were few and far between, and were highly discussed and critiqued, and were only finally accepted if use of these transgressions prevented greater loss to society as a whole.

Starting from Maurya dynasty times, Jus ad Bellum principles got compromised, and eventually even Jus in Bello couldn't be practiced due to the nature of the invaders from the west and northwest.

Europe fought mostly unjust wars, and the humanitarian laws were only adopted after World War II. Many of these laws were based on age-old Indian rules of engagement and dharmic principles. In many cases the Indian principles are more humane and put limits on adharmic behavior during a war.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. A Dorn, Walter, et al. How Just Were America’s Wars? A Survey of Experts Using a Just War Index. Aug. 2015.

2. Adikka. “Ethical Wars: An Exploration of Ramayana & Mahabharata in Sanatana Dharma.” AdikkaChannels - Dharma & Karma: Navigating the Cosmic Balance, 6 Nov. 2023, adikkachannels.com/ethical-wars-an-exploration-of-ramayana-mahabharata-in-sanatana-dharma/#google_vignette. Accessed 15 Aug. 2024.

3. Balkaran, R., and A. W. Dorn. “Violence in the Valmiki Ramayana: Just War Criteria in an Ancient Indian Epic.” Journal of the American Academy of Religion, vol. 80, no. 3, July 2012, pp. 659–90, https://doi.org/10.1093/jaarel/lfs036. Accessed 17 Sept. 2019.

4. Balkaran, Raj, and Walter A Dorn. “Charting Hinduism’s Rules of Armed Conflict: Indian Sacred Texts and International Humanitarian Law.” International Review of the Red Cross, Nov. 2022, international-review.icrc.org/articles/charting-hinduisms-rules-of-armed-conflict-indian-sacred-texts-and-ihl-920.

5. BBC. “BBC - Religions - Hinduism: War.” Bbc.co.uk, 2014, www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/hinduism/hinduethics/war.shtml.

6. Boesche, Roger. 2003. “Kautilya Arthashastra on War and Diplomacy in Ancient India.” Journal of Military History 67(1): 9–38.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

7. Boesche, Roger. “Project MUSE - Kautilya’s Arthasastra on War and Diplomacy in Ancient India.” Muse.jhu.edu, muse.jhu.edu/article/40432.

8. Brekke, Torkel. “The Ethics of War and the Concept of War in India and Europe.” Numen, vol. 52, no. 1, 2005, pp. 59–86, https://doi.org/10.1163/1568527053083430. Accessed 18 Nov. 2019.

9. Carter, Joe. “A Brief Introduction to the Just War Tradition: Jus Ad Bellum.” ERLC, 23 May 2024, erlc.com/resource/a-brief-introduction-to-the-just-war-tradition-jus-ad-bellum/. Accessed 15 Aug. 2024.

10. Curious Sapiens. “Ancient Indian War & Strategies.” YouTube, 9 June 2023, www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zi7r1NMH1QI. Accessed 15 Aug. 2024.

11. Hashmi, SH. “Google Scholar.” Google.com, 2024, scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Ethics+and+Weapons+of+Mass+Destruction%3A+Religious+and+Secular+Perspectives&author=Young+Katherine+K.&author=Hashmi+Sohah+H.&author=Lee+Steven+P.&publication+year=2004&pages=277-320. Accessed 15 Aug. 2024.

12. ICRC Global Affairs Team. “Ethics of Fighting in Ancient Indian Literature - Religion and Humanitarian Principles.” Religion and Humanitarian Principles, 3 Oct. 2022, blogs.icrc.org/religion-humanitarianprinciples/ethics-fighting-ancient-indian-literature/. Accessed 15 Aug. 2024.

13. IndraStra Global. “Revisiting the Ancient Indian Laws of Warfare and Humanitarian Laws.” IndraStra Global, 2017, www.indrastra.com/2017/03/Revisiting-Ancient-Indian-Laws-of-Warfare-Humanitarian-Laws-003-03-2017-0060.html#:~:text=The%20rules%20laid%20down%20in. Accessed 15 Aug. 2024.

14. International Committee of the Red Cross. “What Are Jus Ad Bellum and Jus in Bello?” International Committee of the Red Cross, 22 Jan. 2015, www.icrc.org/en/document/what-are-jus-ad-bellum-and-jus-bello-0.

15. Kolb, Robert. “Origin of the Twin Terms Jus Ad Bellum/Jus in Bello.” International Review of the Red Cross, vol. 37, no. 320, Oct. 1997, p. 553, https://doi.org/10.1017/s0020860400076877.

16. Kosuta, Matthew. “Ethics of War and Ritual: The Bhagavad-Gita AndMahabharata as Test Cases.” Research Gate, 23 Sept. 2020, www.researchgate.net/publication/345399082_Ethics_of_War_and_Ritual_The_Bhagavad-Gita_and_Mahabharata_as_Test_Cases.

17. McDonald, Professor. “Digication EPortfolio :: Jennifer Bourne :: Jus Ad Bellum in the Vietnam War.” Bu.digication.com, 23 Feb. 2014, bu.digication.com/jennifer_bourne/Jus_ad_Bellum_in_the_Vietnam_War.

18. Mr 108. “Lord Krishna’s War Ethics.” Hindu Perspective, Hindu Perspective, 22 Feb. 2013, hinduperspective.com/2013/02/22/hindu/. Accessed 15 Aug. 2024.

19. Pandya, Param. “Tracing the Evolution from the Antiquities: Hindu Tenets on the Law of War.” Ssrn.com, 28 July 2014, papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2971280. Accessed 15 Aug. 2024.

20. Prakash, Siddhant. “Rules and Ethics of Warfare in Ancient India - Siddhant Prakash - Medium.” Medium, Medium, 7 Dec. 2021, medium.com/@siddhant.prakash.singh/rules-and-ethics-of-warfare-in-ancient-india-853547bbe265#:~:text=A%20king%20should%20fight%20only. Accessed 15 Aug. 2024.

21. Project Shivoham. “DHANURVEDAM - a Documentary on Ancient Indian Warfare || Project SHIVOHAM.” YouTube, 31 Dec. 2020, www.youtube.com/watch?v=EJ8eRwq7-IA. Accessed 15 Aug. 2024.

22. The Festival of Bharat. “How Ancient Indians Fought Wars.” YouTube, 19 July 2022, www.youtube.com/watch?v=DyjJY8-bviI. Accessed 15 Aug. 2024.

23. www.wisdomlib.org. “Nitiprakashika, Nītiprakāśikā: 4 Definitions.” Wisdomlib.org, 3 Dec. 2016, www.wisdomlib.org/definition/nitiprakashika#arthashastra. Accessed 15 Aug. 2024.

24. Yalamanchi, Sri Sivani Charan. “Warfare in Ancient Bharat: Part 1 of 2.” Blog.hua.edu, 9 Feb. 2023, blog.hua.edu/blog/warfare-in-ancient-bharat-part-1-of-2.

25. Zuzana Špicová. “Laws of Yesterday’s Wars Symposium - Dharma and Ancient Indian Military Laws in the Mahābhārata - Lieber Institute West Point.” Lieber Institute West Point, 13 Mar. 2023, lieber.westpoint.edu/dharma-ancient-indian-military-laws-mahabharata/.

(The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of New India Abroad)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

E Paper

Video

Comments

Start the conversation

Become a member of New India Abroad to start commenting.

Sign Up Now

Already have an account? Login