Researchers use Indian classical dance to advance robotic mobility

Lead researcher Ramana Vinjamuri said the idea emerged after observing the agility of trained dancers.

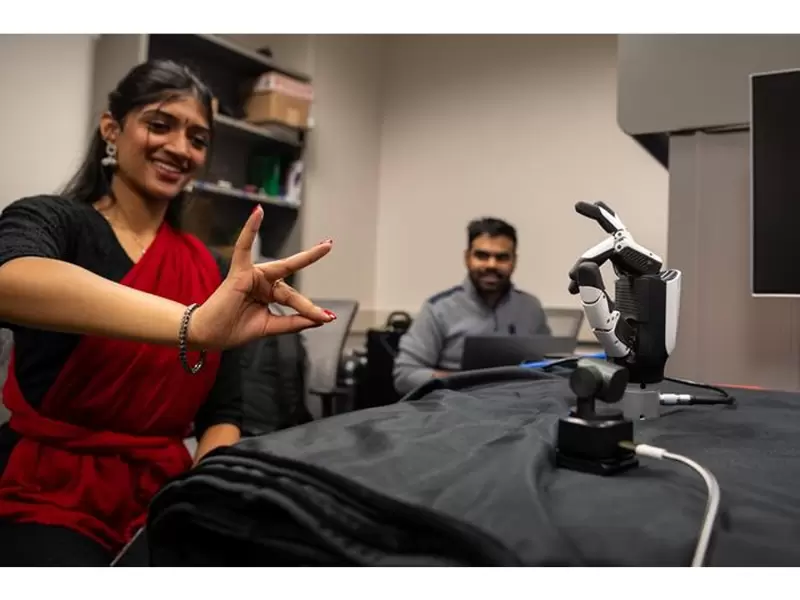

Ashwathi Menon, co-captain of UMBC's Indian fusion dance team, helps demo some of the technology in the lab / Courtesy: Brad Ziegler/UMBC

Ashwathi Menon, co-captain of UMBC's Indian fusion dance team, helps demo some of the technology in the lab / Courtesy: Brad Ziegler/UMBC

Researchers at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC) have drawn on classical Indian dance to decode a more refined system of hand movement that could reshape how robots learn to use their hands.

The study, published Nov. 24 in 'Scientific Reports,' examined Bharatanatyam mudras—precise single-hand gestures central to the dance form—and compared them with everyday hand grasps.

The team found both sets could be broken down into six fundamental "synergies," or coordinated motions that the brain uses to simplify complex actions. But the mudra-derived synergies displayed far greater flexibility.

Also Read: Ritu Raman’s artificial tendons strengthen biohybrid robots

Lead researcher Ramana Vinjamuri said the idea emerged after observing the agility of trained dancers. "We noticed dancers tend to age super gracefully: They remain flexible and agile because they have been training," he said. That insight led the team to explore whether classical dance could reveal a richer set of building blocks for human motion.

Researchers first catalogued 30 natural hand grasps—ranging from holding a bottle to pinching a bead—and identified six core synergies that explained nearly all movement variations. They then applied the same approach to 30 Bharatanatyam mudras and again found six synergies, but with a more versatile structure.

To compare performance, the team attempted to reconstruct 15 American Sign Language letters using each synergy set. The mudra-based system produced significantly more accurate gestures than those generated from natural hand grasps.

"The mudras-derived alphabet is definitely better than the natural grasp alphabet because there is more dexterity and more flexibility," Vinjamuri said.

The research challenges earlier hopes of finding a single universal motion alphabet. Instead, Vinjamuri now envisions a library of task-specific alphabets that could guide robots in activities as varied as cooking, folding laundry, or playing instruments.

The team is testing its methods on a robotic hand and a humanoid robot, using mathematical models to teach machines how to combine synergy units to generate complex gestures. Unlike traditional imitation-based techniques, the new approach mirrors how the brain controls movement, potentially making robotic actions more natural.

The group has also developed a low-cost camera-based system to record and analyze hand motions, which could support accessible rehabilitation tools for patients working through physical therapy at home.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

E Paper

Video

1759163132.png) Anushka Pathak

Anushka Pathak

Comments

Start the conversation

Become a member of New India Abroad to start commenting.

Sign Up Now

Already have an account? Login