Circle Kabaddi must learn from other indigenous sports

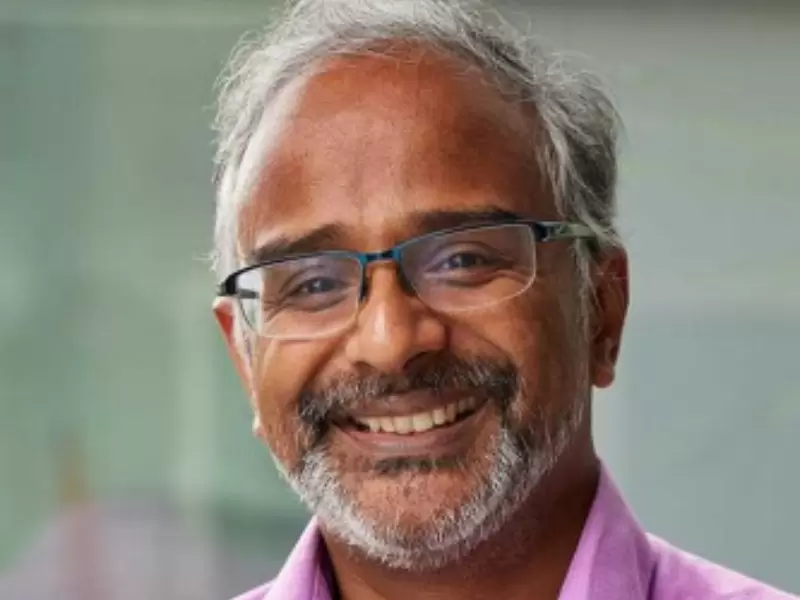

Tejinder Aujla says that Kabaddi enjoys massive popularity, strong cultural roots, and significant private funding, yet lacks professional structure and official recognition

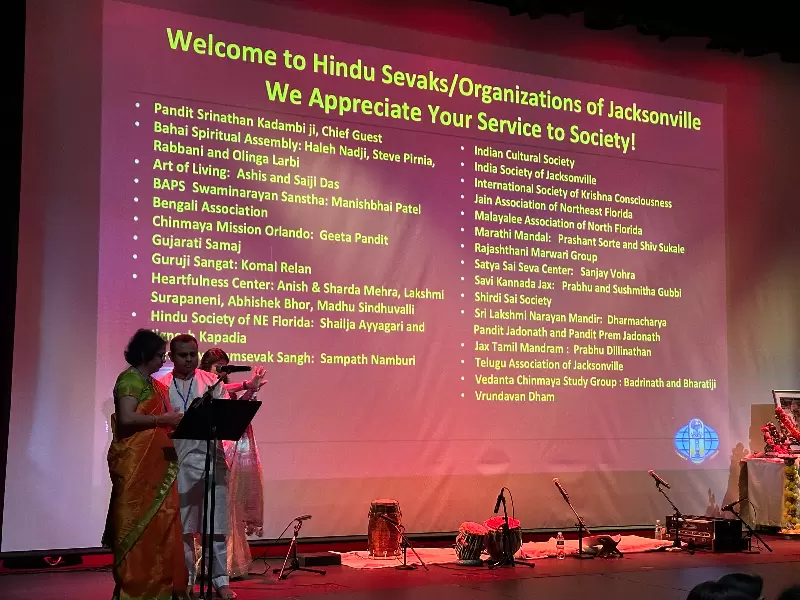

Tejinder Aujla and a Circle Style Kabaddi match / Special Arrangement

Tejinder Aujla and a Circle Style Kabaddi match / Special Arrangement

Can any member of the overseas Punjabi community imagine North America, Europe, or Australasia going without a Kabaddi tournament for the whole of 2026? On the surface, it looks improbable. The ardent fans of this “mother sport” of Punjabis, however, feel that after a year of redemption and introspection, it would re-emerge as a stronger and better-organised sport.

If organised properly, it can be run on the lines of the NBA, NFL, and IPL because of its universal appeal and following.

Circle kabaddi, they say, is like a “phoenix” that re-emerges from its mortal remains.

Is it?

Also Read: Kabaddi: from glory to crisis. What is the way out?

“Yes, it can, provided the introspection or the arduous exercise of restructuring the game at all levels, without disturbing its philosophy, is undertaken with total sincerity,” says Tejinder Singh Aujla, Surrey-based sports thinker and historian. He has already come out with a blueprint to save this ancestral and traditional “Maa Khed” of Punjabis from decaying.

The global community of Punjabis remains greatly enthused by the holding of major international kabaddi tournaments, including World Cups starting around Diwali in November till the completion of the harvesting season in April every year. These tournaments feature teams from India, Pakistan, England, Australia, Germany, France, Italy, the USA, and other nations. There have been occasions when a team from the Sikhs’ highest temporal authority, the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC), also added sheen to these tournaments. This is the only team where players with unshorn hair have come out of India to play in an international tournament.

For the Punjabi community, it is one of the largest entertainment sources, whose budget runs into a couple of billion dollars a year.

Kabaddi, though played the whole year, witnesses a series of prize money tournaments in Punjab during the winter months when hordes of game enthusiasts, including players, head for their homeland to exhibit their physical endowment and skills in outpacing their opponents. Though the FIFKA has announced a complete ban on holding Kabaddi tournaments all over the world throughout 2026, it has made an exception for Punjab, where the elite of world kabaddi is demonstrating its acumen to satiate the appetite of the game enthusiasts.

Though an internationally accepted version of the sport is called “National Style,” where the playing arena is a much smaller rectangular area, what Punjabis cherish is “Circle Style” or “Indian Style,” where a full circle marks the playfield.

Each team is divided into two parts—Raiders and Jaffis (holdbacks or stoppers). When a raider from one team enters the territory of the other team, he heads towards “Jaffis.” One of the four Jaffis tries to hold back the “Raider” who keeps on chanting “kabaddi” without a break in his breath. The moment his chant is broken, he is considered dead, and his team loses a point while the team that succeeds in holding him back gets a point.

A blend of athletics, wrestling, gymnastics, and judo, this ancient team sport with a nearly 4000-year-old history has been serving as a bond between the Punjabi Diaspora and its motherland, Punjab, the land of five rivers, in South Asia.

Though Punjab claims Kabaddi to be their first love, it is the national sport of Bangladesh, while Iran imported an Indian coach before the 2006 Asian Games and has since then come up as a new force in the sport. The British Army, the British Police, and the Irish Army had long been patronising this sport with a regular team.

Since the World Wars saw lots of Punjabis from the then-undivided India fighting for the British forces, both in Asia and Europe, the sport travelled with them to different continents. It was one reason that during the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games, it was included as a demonstration sport.

Though it became a part of the National Games in India in 1938, the sport got a major break in 1990 when it was included in the Asian Games. When India organised the 1982 Asian Games in New Delhi, kabaddi was introduced as a demonstration sport along with the Malaysian sport, sepak takraw. But it was the National Style Kabaddi and not the Punjabi Style or Circle Style. Efforts continue to get this sport included both in the Commonwealth Games and the Olympic Games.

In 1973, the Amateur Kabaddi Federation of India was formed, which has since then tried to rationalise the rules and regulations of the game, but controls only the National Style. Subsequently, the Asian Kabaddi Federation was also formed.

Going by the popularity and its mass appeal, attempts as early as the early 90s were made to hold the World Championships in Kabaddi. It was during this period that Channel 4 in England even ran a couple of documentaries about the origin and popularity of the sport.

In 2009, the Punjab Government introduced the World Cup with prize money. The hosts, India, won the inaugural tournament that featured teams from 12 participating nations, including Iran and Pakistan. The rest of the teams, including those from Canada, the USA, and Spain, comprised only expatriates. A couple of editions of the World Cup followed before they came to an abrupt end.

The turn of the century saw Canada having a Sikh Sports Minister in Bal Gosal. Still, Kabaddi could not get recognition because of huge dissent between various groups claiming to control this “Maa Khed” of Punjabis.

Giving details about his blueprint, Tejinder Aujla says that Kabaddi enjoys massive popularity, strong cultural roots, and significant private funding, yet lacks professional structure and official recognition. This blueprint provides a realistic, legal, and phased reform plan to transform Circle Kabaddi into a credible, sustainable, and nationally recognised sport, without destroying its traditional soul. It is about time for Kabaddi to get recognised and acknowledged by sports authorities from the village or club level to the national level and, ultimately, the international level, with affiliation from respective governments. A time-bound schedule should be implemented over the next 10 years to achieve this goal.

Tejinder Aujla also advocates for one nation, one federation, and one rulebook.

For the safety, discipline, and dignity of players, their registration with the Federation should be mandatory, with transparency over power and preservation of the culture of this sport, with its governance modernised.

The reforms should start by naming the national body, say the Kabaddi Federation of India (KFI), the Kabaddi Federation of Canada, or the Federation of the Kabaddi Associations of the United States. The first duty of the national federations should be to have visionary, statesman-like leadership and get the body registered under the relevant law of the land after drafting and adopting a model constitution aligned with the National Sports Development Code (2011) by making mandatory athlete representation and clearly defining term limits and age limits of office-bearers. The new body should absorb existing Kabaddi bodies as affiliated units rather than competitors.

The next step, says Tejinder Aujla, is to have a national consensus convention by inviting major organisers, promoters, veteran players, coaches, and referees to sign a Circle Kabaddi Unity Charter and freeze parallel claims of authority

Consensus before control.

Standardising the sport by adopting a spectator-friendly approach aligned with established sports should be the next step to elevate Kabaddi into a thrilling, well-organised, and spectator-friendly sport, on par with other established games. The following innovations are proposed, drawing inspiration from best practices in professional sports.

Introducing discipline is very important with a strict code of conduct to ensure respect for opponents, officials, and the spirit of the game. The playfield also needs to be standardised with universal dimensions and a smooth surface of grass or sand.

There should be clear rules leading to team composition, substitutions, and duration of games.

Each team shall consist of eight players. Rolling substitutions will be permitted to maintain pace and intensity. Matches should be played in two halves of 20 minutes each, with a 5-minute halftime interval. Implement an electronic scoring system to display scores, time, and match data in real time.

Introduce a green, yellow, and red card system with clearly defined penalties, like a green card with a 2-minute suspension, a yellow card with a 5-minute suspension, and a red card: immediate ejection from the match.

The participating teams can request a video review; however, a failed review will result in the loss of further review privileges. To ensure smooth conduct of the games, only registered players and match officials will be permitted on the playing field during the game.

Tejinder Aujla has also suggested in his Blueprint that the rules and regulations about reserve players, coaches, and designated areas be assigned outside the field of play to ensure a professional, orderly, and distraction-free environment. He also wants mandatory medical presence to oversee injury protocols, besides conducting doping tests randomly.

His draft contains minute details that can make Circle Kabaddi a true Olympic sport. Any takers?

Discover more at New India Abroad.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

E Paper

Video

Prabhjot Paul Singh

Prabhjot Paul Singh

.jpg)

Comments

Start the conversation

Become a member of New India Abroad to start commenting.

Sign Up Now

Already have an account? Login