Reclaim community narratives

In an era of demographic change and political polarization, history itself has become contested ground.

America's Independence Day / White House (X)

America's Independence Day / White House (X)

As the United States approaches its 250th anniversary, what is at stake in today’s battles over history is far more than textbooks or museum placards. As American Community Media founder Sandy Close reminded participants at a recent briefing, “He who controls the past controls the future. He who controls the present controls the past.” The quote, often attributed to George Orwell, captured the central tension of the moment: a struggle over narrative power.

Who gets to define America’s past, speakers argued, will shape not only how the nation understands itself, but how it governs, who belongs, and whose lives and health are prioritized in the years ahead. In an era of demographic change and political polarization, history itself has become contested ground.

Speakers warned that debates over whose stories will be highlighted in national commemorations are likely to intensify. They cited congressional efforts to influence architectural styles and historical narratives as signs of how politicized remembrance has become.

ALSO READ: Indian American seniors celebrate US Independence Day

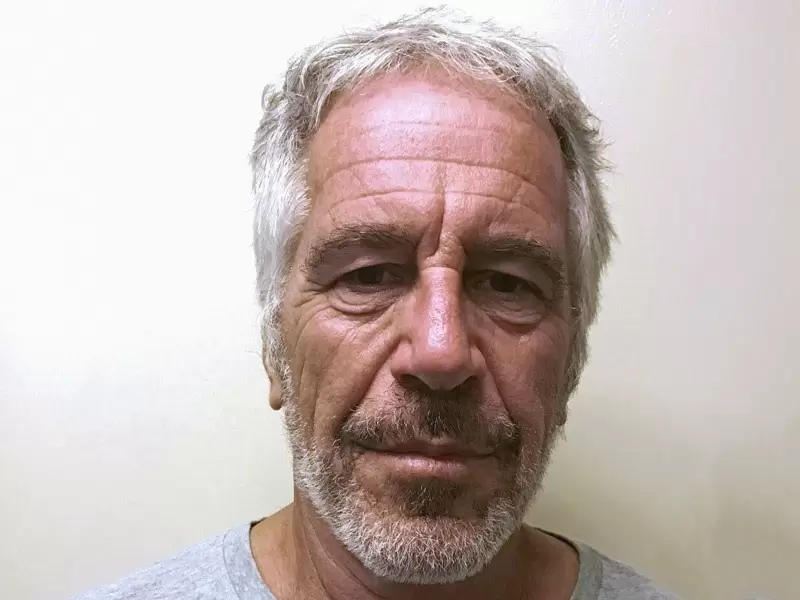

Veteran journalist and author Ray Suarez issued a stark warning about what he described as a coordinated effort by the federal government and conservative media figures to reshape how Americans understand their own history, and who gets to belong within it.

Speaking in the context of his new book, We Are Home, Suarez framed the moment as a pivotal struggle over national identity, one with serious implications for communities of color, particularly Latinos, who now make up roughly one-fifth of the U.S. population.

“We’re watching the national government using its muscle — its funding power, its tremendous ability to influence all parts of our common life — to attempt to revoke or repeal the last 50 years of reconsidering what American history really is,” Suarez said.

According to Suarez, this effort extends across multiple arenas of public life, from school curricula to museum exhibits and even the interpretive text displayed at national monuments. He cited a recent incident in which references to slavery were reportedly removed from a presidential historic site by National Park Service employees, following criticism that such narratives made Americans uncomfortable.

“This idea that it makes white people feel bad, or makes white children feel guilty, it’s baloney,” Suarez said. “This is a power play.”

Suarez argued that the current push seeks to re-center American history around a narrow, exclusionary vision, one that minimizes the roles of Indigenous peoples, African Americans, immigrants and others who shaped the nation from its earliest days. He pointed to the Revolutionary War itself as an example of a deeply multicultural effort involving not only English colonists, but also Dutch, Irish, Scottish, African and Native American participants.

“America has been multicultural since day one,” he said. “It always has been, and it always will be.”

A central concern, Suarez said, is the resurgence of racialized concepts of belonging, including terms such as “heritage Americans” or “legacy Americans,” which have gained traction in far-right discourse. These labels, he noted, suggest that Americans whose families arrived more recently, particularly after World War II, are somehow less legitimate than those with deeper generational roots.

“That idea doesn’t stand up to much interrogation,” Suarez said, noting the vast diversity among European immigrants themselves, many of whom once faced discrimination and exclusion.

Suarez connected this rhetoric to a broader climate of anxiety and backlash, pointing to episodes such as online outrage over the depiction of Black soldiers in World War II exhibits, or the chants of “You will not replace us” at the 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville.

“I think that chant is the central text of this moment,” he said. “It’s about fear, fear of losing the power to dictate who is American and who is not.”

Despite the challenges, Suarez urged journalists, educators and the public to remain grounded in historical fact and inclusive storytelling. He highlighted figures such as Bernardo de Gálvez, the Spanish general who supported the American Revolution along the Gulf Coast, as reminders of the nation’s diverse foundations.

This idea of whiteness, which is a contrived, engineered historical idea, is becoming powerfully asserted in the discourse now.

“You have to share a fantasy that everybody between Cork in Ireland, Krakow in Poland, are somehow the same kind of people. But, at the same time, people in Andalusia and southern Spain and people in Ceuta and Melilla and Casablanca, just across the Straits of Gibraltar, a day’s ferry ride away, are not the same people.”

Untold histories

The struggle over who controls America’s story is not abstract, speakers emphasized. It is deeply personal and still unfolding for people whose histories were erased even as they were being lived.

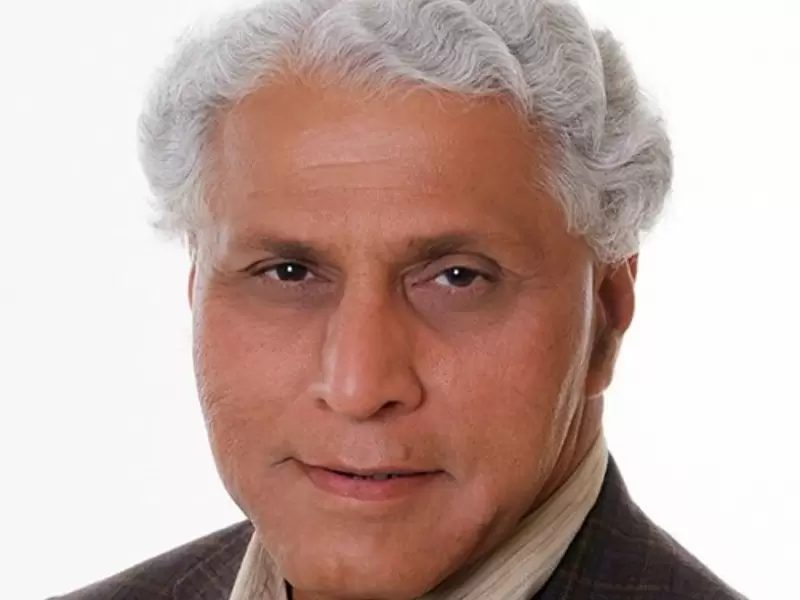

Margaret Huang, president and CEO of the Southern Poverty Law Center, offered a personal account of how that erasure operates and why it matters.

“What else don’t I know?”

Growing up in East Tennessee, Huang said vast chapters of American history were simply absent from her education. “We never talked about Reconstruction. We never talked about the incarceration of Japanese Americans. We never learned about the Civil Rights Movement,” she recalled. Her American history classes focused largely on battlefield death tolls, with little attention to the social and racial struggles that shaped the nation.

It was not until Huang arrived in Washington, D.C., for college that she first learned about Japanese American internment, not in a classroom, but at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. “I was stunned,” she said. “This was part of U.S. history that I had never learned. And it immediately made me wonder what else don’t I know?”

That realization, Huang said, set her on a lifelong path of challenging false narratives and confronting what she described as a persistent unwillingness to grapple with the country’s full history, particularly the stories of people who endured injustice but were denied an official platform to tell it.

Confederate memorials

Huang pointed to Confederate memorials as a striking example of how public memory has been deliberately shaped. Research by the Southern Poverty Law Center found that monuments honoring Confederate leaders exist in nearly every state far beyond the geography of the Civil War itself. Crucially, she noted, most were not erected immediately after the war, but decades later.

“These memorials were put into place 60 to 80 years later,” Huang said, during the rise of Jim Crow and in direct response to demands for civil rights. “They reflect a moment when white supremacy was being reasserted.”

Although hundreds of Confederate monuments have been removed since 2015, Huang said more than 2,000 remain, continuing to elevate figures who fought against the United States while marginalizing those who suffered under the systems they defended.

Counter-narratives are emerging not from Washington, but from local communities.

Huang also criticized recent efforts to reverse decisions by the U.S. military to rename bases previously honoring Confederate generals, decisions that had followed years of expert review and community consultation. “Extraordinary heroes were identified,” she said, “people who reflect the beautiful diversity of this country.” Reverting to Confederate names, she argued, sends a clear message about whose history is valued.

Yet Huang emphasized that some of the most powerful counter-narratives are emerging not from Washington, but from local communities. She highlighted Montgomery, Alabama, where grassroots efforts are reshaping how history is remembered and how its consequences are addressed in the present.

The story of ‘mothers of gynecology’

One such effort centers on the long-overlooked story of the “mothers of gynecology,” enslaved women who were subjected to brutal, nonconsensual medical experimentation by 19th-century physician J. Marion Sims. While Sims has long been celebrated as a founder of modern gynecology, Huang said the women whose suffering made his work possible — Betsy, Anarcha and Lucy — were erased from the narrative.

Artist and activist Michelle Browder, Huang explained, spent years trying unsuccessfully to have Sims’ statue removed from the Alabama State House grounds. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Browder took a different approach: She built a memorial honoring the women themselves, forged from metal and medical instruments, reclaiming their story on their own terms.

Browder’s work, Huang said, does more than correct the historical record. It draws a direct line from past abuse to present-day inequities. Nearly half of Alabama’s counties, she noted, lack access to obstetric or gynecological care. Proceeds from the memorial now fund a mobile clinic providing reproductive health care across the state.

“It’s about telling the truth,” Huang said, about harm, about resilience and about the ongoing fight for equity. “We can’t tell the stories of how Americans overcame these wrongs if we don’t acknowledge the harm that was done to begin with.”

Together, speakers argued, these untold histories reveal why the battle over America’s past is also a battle over its future, and why communities living with the consequences of erasure continue to demand the right to define themselves, even in the face of fear.

Discover more stories on NewIndiaAbroad

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

E Paper

Video

Ritu Marwah

Ritu Marwah

.jpg)

.jpg)

Comments

Start the conversation

Become a member of New India Abroad to start commenting.

Sign Up Now

Already have an account? Login