A tale of harmony builds this Ravana for Dussehra flames in Punjab

The effigy is a blend of technology and art, but the heart of the story lies in Muslims and Hindus working side by side.

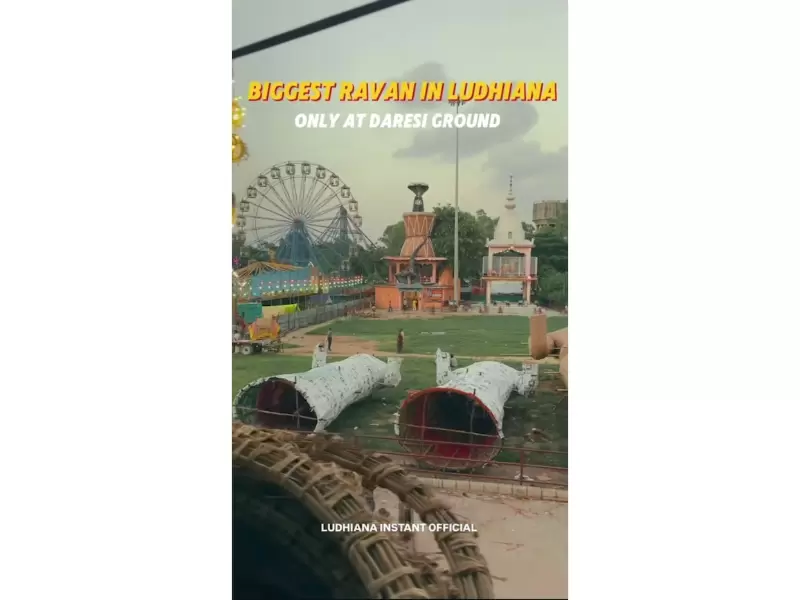

The biggest Ravan effigy in Ludhiana. / INSTAGRAM/@ludhianainstantofficial

The biggest Ravan effigy in Ludhiana. / INSTAGRAM/@ludhianainstantofficial

In the bustling Punjabi city of Ludhiana, the arrival of Dussehra is marked not only by the crackle of fireworks and the burning of Ravana effigies, but also by a quiet story of shared tradition. For more than a century, a Muslim family from Agra has been at the center of these celebrations, building the towering figures that go up in flames each year.

Sohel Khan, a fifth-generation artisan, spends half the year in Punjab shaping bamboo, paper, and fireworks into Ravana, Kumbhakarna, and Meghnath. This season his team of about two dozen craftsmen, including Hindus, is creating a 121-foot effigy of Ravana, reportedly the tallest in Punjab, to be burned at Ludhiana’s Daresi Maidan.

“We begin six months in advance. Doing this work makes us very happy because we are celebrating a Hindu festival together,” Khan says. “It’s not just about the effigy. It’s about harmony.”

The scale of the work is immense. Around 500 bamboo poles form the skeleton. More than a quintal of paper covers the frame. Explosives are packed inside, and this year the effigy will be fitted with special fireworks from Lucknow.

What sets the mammoth structure apart is its modern engineering. “The effigy has two remotes. With the first, the lower part of Ravana’s mouth will catch fire, and with the second, the upper half will ignite,” Khan explained.

The project costs around INR500,000 (appx $5,600), but the investment is more than financial. For the artisans, their success is measured by the blaze. “The sooner Ravana catches fire, the more successful we feel,” says craftsman Aqeel Khan. “If it takes too long, it feels like all our hard work has gone in vain.”

Over the years, they have also adapted their craft. Imported water-resistant paper has replaced the plastic-laced sheets once used, cutting down on toxic smoke and making the effigies sturdier against weather.

Just as important as the scale and spectacle is the team itself. Hindus and Muslims work side by side in the workshop, bound by friendship and trust. “I am a Hindu and have been helping a Muslim family make effigies of Ravana for many years,” says artisan Naresh Sharma. “We all come together to create an example of brotherhood.”

For Sohel Khan, carrying forward the family tradition is about more than livelihood. “It makes us proud that we can contribute to this festival and show that it belongs to everyone,” he says.

When the 121-foot Ravana rises into the Ludhiana night and collapses in a shower of sparks, it will be more than the familiar story of good triumphing over evil. It will also be a reminder that festivals carry their deepest meaning when celebrated together.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

E Paper

Video

1759953093.png) Staff Reporter

Staff Reporter

Comments

Start the conversation

Become a member of New India Abroad to start commenting.

Sign Up Now

Already have an account? Login