When a sacred symbol is misread: A Hindu child’s experience in a London school

The child’s experience was shaped not by what he did, but by how a visible marker of his faith was interpreted by authority figures.

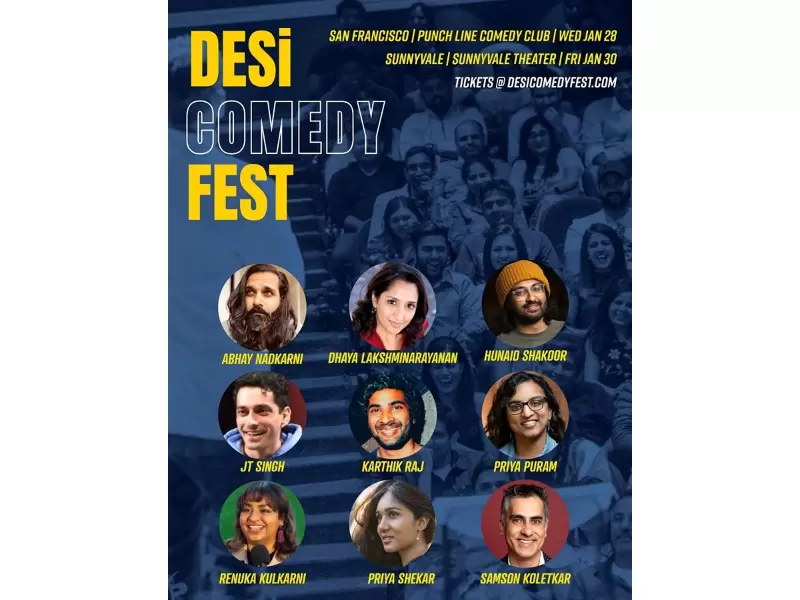

Vicar’s Green Primary School, London / Image:insightuk.org

Vicar’s Green Primary School, London / Image:insightuk.org

The recent report by Insight UK concerning an eight-year-old Hindu pupil at Vicar’s Green Primary School in London has unsettled many within the global Indian diaspora.

According to the organization, the child was repeatedly questioned by school staff for wearing a Tilak-Chandlo, a traditional sacred mark on the forehead eventually leading to social withdrawal, removal from positions of responsibility, and ultimately his departure from the school.

While the incident may appear, at first glance, to be a local administrative dispute over school policy, it points to a deeper institutional failure: a lack of cultural literacy in environments that are otherwise committed, at least in principle, to diversity and inclusion. What is being exposed here is not misconduct by a child but a systemic inability to recognize and understand non-Western religious expressions.

Also Read: Hindu values, the U.S. Constitution, and a silent American contradiction

To appreciate why this matters, one must first understand what the Tilaka actually represents. The Tilaka is a traditional mark worn on the forehead by many Hindus, and it is neither a modern invention nor a political statement. It is among the oldest continuously practiced spiritual customs in the world, with origins tracing back to the Vedic period, around 1500 BCE.

Its earliest form emerged from Yajna, sacred fire rituals central to early Hindu worship where participants applied purified ash (Bhasma) to the forehead. This act symbolized mental purification, humility, and awareness of life’s impermanence. It was never intended as a marker of group identity or public assertion but as a personal reminder of ethical discipline and inner restraint.

Over centuries, Hindu philosophical texts known as the Upanishads, which focus on self-knowledge, consciousness, and moral conduct, formalized the practice further. Texts such as the Vasudeva Upanishad and the Kalagni Rudra Upanishad describe different styles of Tilaka, including horizontal lines associated with followers of Shiva and vertical lines associated with followers of Vishnu (Hindu God).

These variations were not badges of allegiance in a social or political sense, but symbolic ways of treating the human body as a sacred space governed by values rather than impulse. To wear a Tilaka, therefore, is to carry one’s inner discipline into daily life, a private act of devotion, not a demand for recognition or exemption.

Equally important is the fact that the placement of the Tilaka is not arbitrary. Hindu traditions describe the centre of the forehead as a focal point of attention and awareness, a concept articulated through what is often called yogic anatomy, a pre-modern framework for understanding the mind–body connection. Interestingly, this aligns in notable ways with modern physiological insights.

From a medical perspective, the area between the eyebrows lies above the prefrontal cortex, the region of the brain associated with concentration, emotional regulation, and decision-making. The gentle pressure applied while marking the Tilaka functions much like acupressure, a technique widely recognized for its calming effects. Traditional explanations spoke of mental clarity; contemporary neuroscience speaks of stress modulation and cognitive focus. The language differs, but the underlying observation is strikingly similar.

Also read: Buddha statue built in place of Hindu one on disputed Thai-Cambodia border

The materials traditionally used for Tilaka application also reflect a practical logic. Sandalwood paste (Chandan), for instance, has natural cooling properties. In classical Indian medicine (Ayurveda), the forehead was understood as an area where mental strain and heat accumulate during prolonged intellectual activity. Applying a cooling substance was believed to promote emotional composure and sustained attention. This is now supported by growing research into temperature regulation and cognitive performance.

Other materials, such as turmeric (Kumkum) and refined ash, were valued not only symbolically but for their antibacterial and antiseptic qualities. Long before the advent of modern disinfectants, these substances integrated basic hygiene into daily ritual life. Seen in this full context, the Tilaka is neither ornamental nor ideological; it is a millennia-old mindfulness practice that blends symbolism, psychology, and bodily awareness.

What makes the Vicar’s Green case particularly troubling is not the existence of a uniform policy, but how it was applied to a child too young to articulate or defend his cultural practice.

According to news reports, the eight-year-old pupil was repeatedly questioned by staff about the Tilak on his forehead, despite explanations from the family. Over time, the scrutiny reportedly led to the child becoming socially withdrawn. He was removed from positions of responsibility within the school and, eventually, the family felt compelled to withdraw him altogether.

There was no allegation of misconduct, disruption, or proselytization. The child’s experience was shaped not by what he did, but by how a visible marker of his faith was interpreted by authority figures. For a young pupil, repeated questioning over a personal religious practice can blur into a sense of suspicion, conveying, however unintentionally, that something about his identity was a problem to be managed rather than understood.

Misreading such a practice as a political signal or institutional disruption says little about the wearer’s intent and much about the observer’s unfamiliarity. This gap becomes particularly troubling when it occurs within public institutions governed by equality law.

The UK Equality Act 2010 explicitly protects religion and belief as core characteristics and places a statutory duty on schools to avoid indirect discrimination where apparently “neutral” policies, such as uniform codes, disproportionately disadvantage certain religious groups. The Act also requires institutions to foster good relations between communities, a duty that begins with understanding rather than interrogation.

Importantly, the Vicar’s Green case is not an isolated anomaly. Independent research suggests that Hindu pupils in the UK have faced similar scrutiny for years, often without formal acknowledgement. A 2023 briefing by the Henry Jackson Society titled Anti-Hindu Hate in Schools revealed that over half of Hindu parents surveyed reported their children had experienced anti-Hindu prejudice in UK schools.

Yet fewer than one percent of schools responding to Freedom of Information requests admitted to recording any such incidents over a five-year period, pointing to a serious institutional blind spot.

The report also highlighted a pedagogical issue: Hinduism is frequently taught through a Western, Abrahamic framework that fails to capture its lived practices. This misrepresentation can unintentionally legitimize peer bullying or teacher-led suspicion of sacred symbols like the Tilaka, treating them as anomalies rather than protected expressions of belief.

The contrast with other Western democracies is instructive. In the United States, constitutional protections under the Free Exercise Clause require schools to demonstrate genuine disruption before restricting religious expression, with landmark judgments affirming that students do not shed their rights at the school gate. In Canada, the principle of “reasonable accommodation” obliges institutions to adjust rules for religious practices unless doing so causes undue hardship, often framing such moments as opportunities for multicultural education rather than administrative conflict.

Taken together, these examples suggest that the issue is not the presence of religious symbols but the absence of institutional preparedness to engage with them. Addressing this gap requires more than reactive apologies.

It demands standardized reporting of faith-based incidents, culturally accurate religious education, and targeted training for safeguarding and leadership staff so that sacred symbols are recognized for what they are and not misconstrued as unexplained or suspect markings.

When an institution treats the Tilaka with suspicion, it does more than misunderstand a child; it dismisses a 3,000-year-old contribution to human approaches to mindfulness, discipline, and well-being. For the global Hindu diaspora, the Tilaka remains a quiet, non-intrusive expression of heritage and values. Moving from scrutiny to respect is not an act of concession but a necessary step toward the inclusive society that modern democracies claim to uphold.

The writer is an author and columnist on history and civilizational issues.

(The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of New India Abroad.)

Discover more on New India Abroad

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

E Paper

Video

Dr. Vinay Nalwa

Dr. Vinay Nalwa

Comments

Start the conversation

Become a member of New India Abroad to start commenting.

Sign Up Now

Already have an account? Login