Macaulay is an “important," not an “outstanding” character for India

Many of us may not know that Macaulay, at the age of eight, wrote a convincing essay on the desirability of converting heathens to Christianity.

Thomas Babington Macaulay / National Portrait Gallery: Wikipedia

Thomas Babington Macaulay / National Portrait Gallery: Wikipedia

In his Wall Street Journal column, ‘East is East,’ Sadanand Dhume, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, presents a romanticized view of Macaulay, as if he were a reformer and educationist for India.

Thomas Babington Macaulay was a ‘historian’ who also served as the British Secretary of War (1846-48). Dhume writes (Western Education has Lifted India, December 3, 2025) that “Macaulay was a self-made man elevated to the pinnacle of Britain’s ruling class, thanks to his precocious intelligence and scholarly brilliance. Before he was 8, he had completed an outline of world history and a poem in the style of Sir Walter Scott. He reportedly knew seven languages, including ancient Latin and Greek.”

Also Read: Indian Americans: Are we our own worst enemy?

Access to English, indeed, has helped Indians obtain a ‘modern’ education and become more competitive in the Western job market. That is not to say that Indians have become the innovators and creators because of it. India has been doing much better, both educationally and professionally, without English. India, with its storied knowledge system, was already a knowledge powerhouse before any British landing ashore and colonizing the country.

Also, neither English nor the English-language education needed Macaulay to set foot in India. Other British colonies also adopted English and English language education without Macaulay.

On the other hand, Macaulay was responsible for running India’s native education and the knowledge system to the ground. Noted Indologist and linguist Kapil Kapoor often says that India, almost overnight, became an illiterate society from being one of the most educated knowledge societies, thanks to Macaulay. Historian Dharampal’s book ‘The Beautiful Tree: Indigenous Indian Education in the Eighteenth Century makes this fact abundantly clear. According to Arvind Sharma (The Rulers Gaze: A Study of British Rule Over India From Saidian Perspective), “An even more serious example of the regress of Indian society under the colonial rule is provided by the dismantling of the native educational system in order to replace it with the British, with the result that Indians were made illiterate by destroying it to justify the need to educate them.”

Sharma further writes that Macaulay is an “important” rather than an “outstanding” character in the context of India. Macaulay found Indians a “debased” race and “decomposed society,” comparable to 5th-century Europe (after the Roman Empire’s collapse).

Many of us may not know that Macaulay, at the age of eight, wrote a convincing essay on the desirability of converting heathens to Christianity. Upon his arrival in India, Macaulay travelled from Madras (now Chennai) to Ooty to meet Governor-General Bentinck—a distance of 400 miles—on the shoulders of Indian men, and then back: Twelve bearers—six at a time—carried his palanquin down to Madras, as he reclined and read Theodor Hook’s Love and Pride.

It has become fashionable among some rightwing conservatives, of late, to justify slavery and colonialism. Dhume’s commentary on Macaulay is an apologia for colonialism.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

E Paper

Video

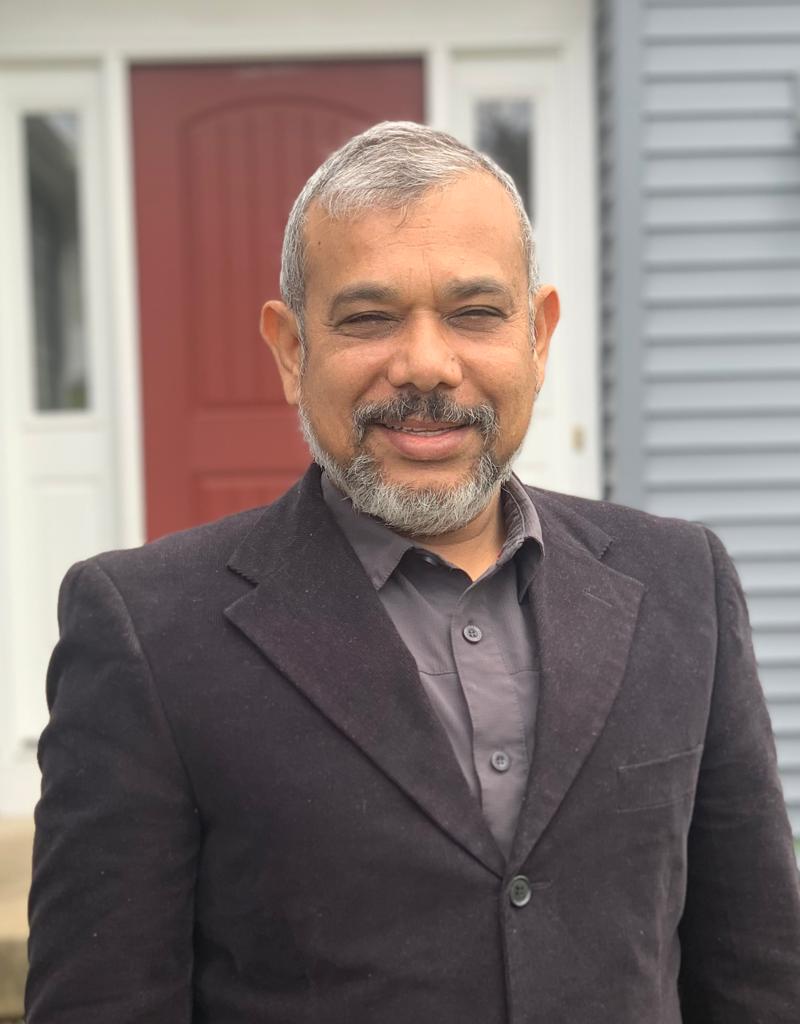

Avatans Kumar

Avatans Kumar

Comments

Start the conversation

Become a member of New India Abroad to start commenting.

Sign Up Now

Already have an account? Login