“If Kashmir hurt you, Bengal will haunt you” — Vivek Agnihotri and Pallavi Joshi on completing the files trilogy

Pallavi Joshi labeled the movie as a deeply personal experience and said that she felt nervous, excited and sad.

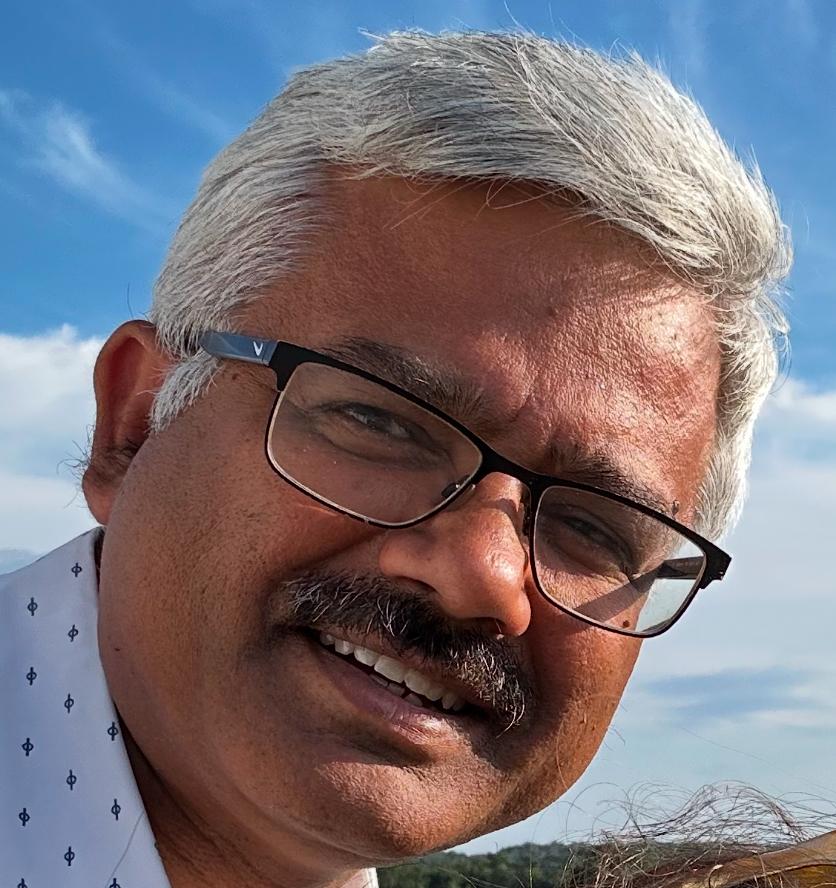

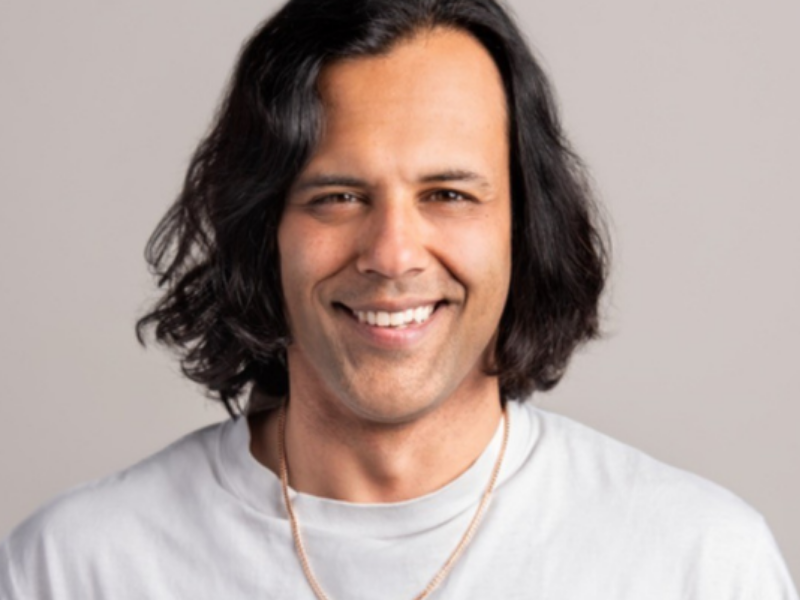

.jpg) Director Vivek Agnihotri with protagonist Pallavi Joshi / Lalit K Jha

Director Vivek Agnihotri with protagonist Pallavi Joshi / Lalit K Jha

After The Tashkent Files and The Kashmir Files, filmmaker Vivek Ranjan Agnihotri and actor-producer Pallavi Joshi have released the final instalment in their trilogy: The Bengal Files. The film had its exclusive world premiere in Washington, D.C., on July 20 as part of the "Never Again Tour." The duo sat down with this correspondent for an emotional and revealing conversation about their decade-long journey, forgotten Indian history, and the haunting relevance of Bengal’s past to today’s politics.

Q: What is The Bengal Files about, and why did you choose Bengal as the focus of the final film in your trilogy?

Vivek Ranjan Agnihotri: So you’ve seen this trilogy—first was the right to truth (The Tashkent Files), second was the right to justice (The Kashmir Files), and this one is about the right to life. People generally don't know this, but when we talk about Partition, most assume it happened only in Punjab. The real playground of Partition was Bengal. That’s what this film explores.

All the leaders agreed to Partition because of the bloody, terrifying violence. This film studies whether that violence in Bengal stopped or not. And if it hasn’t, are we really free? And if we are, why are we so helpless and letting it happen? It moves back and forth between 1946—Direct Action Day, Noakhali genocide—and what’s happening in Bengal today. It makes you wonder: what’s your role in all this? Is Bengal going to become another Kashmir?

Q: Pallavi ji, how has this trilogy affected you personally?

Pallavi Joshi: It’s been a deeply personal journey. We began research for the first film in 2015. Ten years later, here we are—three films completed, thanks to our excellent research team. With the first two films, I was excited. With The Bengal Files, I felt we were addressing an extremely important chapter of our history.

As screenings began yesterday, I felt nervous, excited, and also a deep sadness. This is the end of the trilogy. We didn’t even realize how the last decade passed—we were immersed in research and collaboration. This series gave us the opportunity to work with our children too—Vivek’s assistant and my production support. I thank God and the audience who have embraced these films.

Even though the Files series is over, our journey isn't. Future projects may not carry the "Files" label, but they’ll still delve into lesser-known histories. Only when you know your yesterday can you build a better tomorrow.

Q: Why do you think these episodes of Indian history—like Direct Action Day—were never taught or remembered?

Vivek Ranjan Agnihotri: Even I wonder why. You’ll never find a Jewish child who doesn’t know about the Holocaust. Or a Sikh child unaware of Operation Blue Star. Or a Rwandan who doesn’t know about the genocide. But Hindus? Despite 1,200 years of persecution, they don’t know their history.

Nobody knows about Direct Action Day. If it had happened in the West, they would’ve made memorials, books, documentaries. We didn’t. That’s why I made this film. Every scene, every line is based on deep research—Gandhi's words, Jinnah's, and headlines from The New York Times, Time, Life magazine. If I, someone politically aware, didn’t know about it, how would others?

Pallavi Joshi: Let me share something—someone in our office asked if we’re screening in Boston. I said no. He replied, “But I read so much about the Boston Tea Party.” When I asked where, he said “our history books.” So our children learn about the Boston Tea Party, but not Direct Action Day or the trauma our country went through.

That’s a systematic erasure of history. We keep our citizens in a sanitized bubble—“India Shining”—but if you don’t know your past, how will you prepare for your future?

Q: Do you consider what happened in Bengal a genocide or a holocaust?

Vivek Ranjan Agnihotri: I don’t care what word the West uses—genocide, holocaust. They create hierarchies of pain. What matters is: 40,000 people were killed in four days. The same number thrown into the Bay of Bengal.

Partition was the largest displacement in human history. In Bengal, signs said “Dogs and Indians Not Allowed.” That puts Indians below dogs. Maybe people were too exhausted after Partition to talk about it.

Also, the moment you talk about Bengal, you have to mention Subhas Chandra Bose. And Congress—Delhi—never wanted to highlight Netaji. Maybe that’s why this history was buried.

Q: How do you view today’s situation in Bangladesh —political violence, attack on minority Hindus?

Vivek Ranjan Agnihotri: I don’t care what happens in other countries, but I do care about its impact on India. India is surrounded by radical Islamic states. For them, Partition is still an unfinished project. Now Bangladesh and Pakistan, for the first time ever, conducted joint military drills.

That’s not because they love each other. It’s for India. Today, Bengal’s eastern border is as volatile as Kashmir’s. There’s infiltration. Illegal immigrants are empowered with fake IDs and turned into vote banks. That’s why Bengal has the highest rate of political and electoral violence in the world.

Q: What can our leaders learn from The Bengal Files?

Pallavi Joshi: Honestly, nothing. If leaders wanted to act, they’d have done it long ago. They know this history better than us. We filed RTIs during The Tashkent Files—we got no answers. Just a response that one page exists, and it’s “classified.”

Governments have access to everything. If they haven’t acted, it means politics has trumped truth.

Q: Do you believe the files and records should be declassified?

Pallavi Joshi: Absolutely. In any mature democracy, after 50 years, records are declassified. But even after 60 years of Subhas Chandra Bose’s death, we weren’t given anything. What are they hiding?

Q: What should be India’s top priority now?

Vivek Ranjan Agnihotri: Partition happened due to criminal violence. Muslim League called it an “unfinished project.” First Kashmir, now Bengal. Same playbook—demographic change, inch by inch.

If I were the Prime Minister, I’d make religious violence a “rarest of rare” crime with the strictest punishment. That fear must exist. But our system is so broken—it’s not enough to repair it. We must rebuild it.

Q: Based on your research, could our leaders have prevented this violence?

Vivek Ranjan Agnihotri: Of course. Leaders can do anything. Jinnah wanted Pakistan—he got it. He won. We lost. Our leaders lost. So yes, they could have stopped it.

Lalit K Jha

Lalit K Jha

.jpg)

Comments

Start the conversation

Become a member of New India Abroad to start commenting.

Sign Up Now

Already have an account? Login