India-US relations register unprecedented growth despite challenges

The main highlight this year was Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s state visit to the United States in June

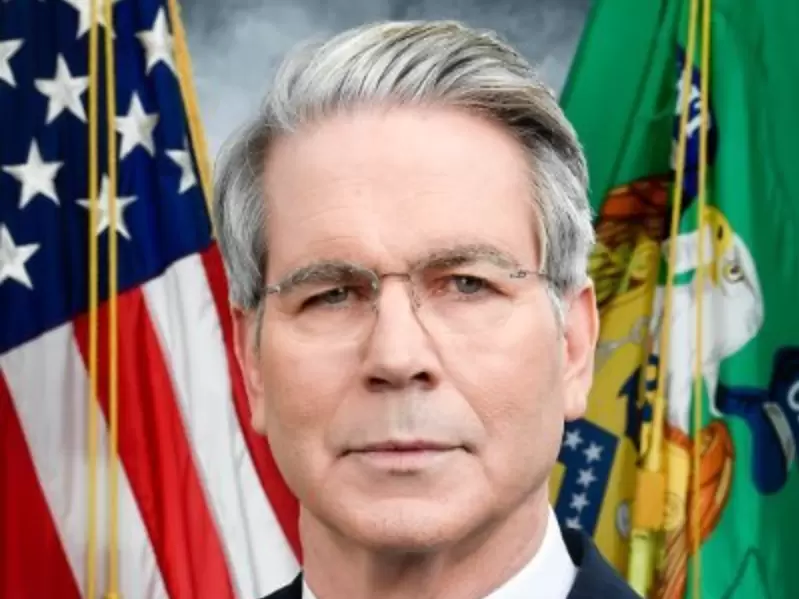

PM Narendra Modi and US President Joe Biden at the White House. / X/@narendramodi

PM Narendra Modi and US President Joe Biden at the White House. / X/@narendramodi

Once there was more rhetoric than substance in Indo-US relations, barring the notable exception of the pathbreaking 2005 civil nuclear agreement. Today there is more substance than rhetoric and pathbreaking agreements are too many to count. More importantly, policy disagreements such as the one on the Ukraine war are managed calmly without public acrimony.

The main highlight this year was Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s state visit to the United States in June complete with a ceremonial reception and a mile-long joint statement detailing cooperation in almost every domain of human endveavour from space to under the sea.

The highly successful visit showed President Joe Biden’s commitment to the partnership – the two leaders met on all three days that Modi was in Washington to launch several new projects – from a “tech handshake” to bring the titans of technology in both countries closer together to efforts to create links between the two health and education systems.

Biden paid a return visit in September for the G-20 summit and thanks largely to his accommodative stance, India was able to get a final communique. Both the US and Europe softened their condemnation of Russia President Vladimir Putin, whose war against Ukraine has created myriad diplomatic minefields for India over time.

Undoubtedly, a major reason for the thickening of Indo-US relations is China which both countries see as a major security threat. If the 2020 Galwan crisis with China when 20 Indian soldiers died in a border clash clarified New Delhi’s mind about Beijing’s intentions, American awakening to China came under former president Donald Trump who turned US policy around.

China’s multiple aggressions across the Indo-Pacific over the past few years against US allies have removed all doubt in Washington that Beijing wants to wrest the No.1 position from the US. Both India and the US have a common interest in countering China.

The year began with the two national security advisers, Jake Sullivan and Ajit Doval, launching a far-reaching Initiative on Critical and Emerging Technologies or iCET, an idea that aligns India and the US on all key fronts – political, strategic, technology and defence. The promise of iCET quickly led to many offshoots, most prominently in the realm of defence cooperation.

In just a few months significant progress was made as confidence and trust grew. Pentagon is an eager participant in India’s plan for self-reliance – a major deal to co-produce GE jet engines in India was finalised, another to buy 31 Predator drones parts of which will be assembled in India is almost complete, agreements are in place to make India a logistics hub for maintenance and repair for friendly navies and air forces in the Indo-Pacific, support to integrate Indian defence companies into US supply chains has grown and restrictive US export controls are being tackled.

India and the US took great leaps in the realm of space with India signing the US-led Artemis Accords which establish principles to guide space exploration. Also, NASA agreed to train ISRO astronauts for a joint mission to the International Space Station in 2024 to say nothing of the interest in India’s space startups by US companies for joint ventures.

On the trade front, in a surprising move the two countries settled all seven outstanding trade disputes at the World Trade Organisation with mutual agreements and adjustments. Meanwhile, the US became India’s largest trading partner in 2022 with two-way trade at 191 billion, a figure expected to be overtaken when data for 2023 becomes available.

Most importantly, the strategic partnership has matured to a level where serious challenges are dealt with calm and consideration. If 2023 recorded unprecedented progress on multiple fronts, it also threw a big boulder in the path.

The US Department of Justice unveiled an indictment against an Indian national, Nikhil Gupta, who allegedly worked with an Indian government official to plot the assassination of a New York-based Khalistani. The plot was foiled but the revelation damaged trust between Washington and New Delhi, especially between the two intelligence set-ups.

The US indictment came a few months after the killing of a Canadian Khalistani, Hardeep Singh Nijjar, in Surrey on June 18 which led Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to make a statement in Parliament about “credible evidence” of Indian government’s involvement. But unlike Trudeau’s public attack, US officials shared information behind closed doors with top Indian officials and pushed for accountability.

The White House dealt with the alleged plot – foiled by an informant working for US intelligence – without public posturing while continuing to keep the bilateral agenda moving. Biden raised the issue himself with Modi and sent several high-level officials to New Delhi, including the Director of CIA William Burns and Director National Intelligence Avril Haines. NSA Sullivan also raised the issue with his Indian counterpart, Doval when they met in Saudi Arabia in August to convey the gravity of the issue.

The US has asked that India hold those responsible to account and give an assurance that it won’t happen again. India has appointed an enquiry committee to look into the whole affair. How a solution that is acceptable to both sides is crafted will become apparent with time. What’s clear is neither side wants the relationship derailed by the problem and wants to continue building the partnership.

The author is a Columnist and author of “Friends With Benefits: The India-US Story.”

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

E Paper

Video

Seema Sirohi

Seema Sirohi

Comments

Start the conversation

Become a member of New India Abroad to start commenting.

Sign Up Now

Already have an account? Login